The Return

The pandemic recedes, New Yorkers emerge resilientThe Return

The pandemic recedes, New Yorkers emerge resilientNew York has a buzz again, if somewhat hushed. It’s heard, in passing, on subway platforms resuming 24-hour service, in classrooms that are seeing students again, and in the restaurants that have slowly invited customers inside. On Zoom calls, bosses are trying to coordinate how workers climb back into skyscrapers.

More than a year after New York City became the global epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic—in a country unable to contain its spread—there’s a sense of hope. There’s reason for that, too. New Yorkers banded together with mutual aid. They promoted one another on social media. They have largely complied with mask mandates intended to reduce the airborne spread of the virus, even during dark winter months when the virus had another surge. Perhaps more importantly, vaccination rates are up.

Politicians in City Hall and the state capitol say it’s time for full reopening. Mayor Bill de Blasio calls it “the summer of New York City.” Gov. Andrew Cuomo says vaccines are key to winning the war against COVID-19. And in Washington, a fully vaccinated President Joe Biden is taking off his mask, per new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines. But there’s more nuance than daily briefings meant to boost public confidence. Vish Viswanath, a professor of health communication at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, prefers to describe this next phase as a transition back to normal, one marked by continued face covering mandates depending on location, and hybrid office spaces partly online and somewhat in person. It helps prepare people mentally as public health restrictions get lifted. “You plant a seed,” he said. “It’s a transition, not a complete reopening.”

In a city with vast disparities across race and class, the effects of the virus vary by borough, and by street—of who has access and information, and who doesn’t. The coronavirus, which mutates with variants across the world, is likely to stay with the global city for the future. What remains is how people cope and how they readjust.

As people step outside, unmasked or not, the buzz is low but audible. It’s not flag-waving. It’s quiet, empirical. When does traffic once again hit Midtown Manhattan? How does neighborhood composting work, again? In de Blasio’s New York summer, what does Coney Island look like?

NY City Lens talked to New Yorkers on how they view a return of their city. Here are their stories. — Eduardo Cuevas

The Bike Wizard

The Bike Wizard

At a Washington Heights repair shop, pandemic business is booming

“People here like to ride their bicycles, they don’t want to take the train. They’re going to be independent of the train.”

![]()

Victor De Leon, 69, never has much time to talk inside his Washington Heights bike shop nowadays. Warm weather means business. And oddly, the pandemic has been lucrative, most likely, he thinks, because even more New Yorkers have opted for cycling as an alternative to the subway.

“We try to help you, you know, to do the best I can,” said De Leon, a stout man with grizzled hair, whose leathered hands are oil-stained. His rumpled mechanic uniform has his name on it.

His business, named Victor’s, normally closes during the winter months. But as the city awakens from a pandemic snooze this spring, the shop is open every day, even Sunday, to handle more customers. De Leon and his two-man crew fix about 25 bikes a day. He doesn’t expect this to change for the time being.

“With the pandemic, the business went up,” he said. “People here like to ride their bicycles, they don’t want to take the train. They’re going to be independent of the train.”

De Leon’s team assembles or repairs bikes in just a couple of hours. It’s quite a feat, especially when compared to lower Manhattan shops that can take days just to book an appointment, and cost up to twice what De Leon charges. His clients are mostly local cyclists from the neighborhood and delivery workers, who allowed people to quarantine at home while they fetched groceries and meals.

While he works, De Leon is quiet, head down as he focuses on the latest fix. Occasionally, as customers talk on the array of seats and stools in the shop, De Leon chimes in — about bikes, the neighborhood, or family.

The small storefront’s awning on Broadway is painted red, white, and blue — the colors of De Leon’s native Dominican Republic — where most Washington Heights residents also trace their roots. De Leon has loved bikes since he was a teen in his hometown, Santo Domingo. As soon as he started pedaling, he says, he also began fixing bikes for friends and families. Cyclists, he said, are supposed to understand bicycles’ problems. Reviews from clients on Yelp say De Leon can spot flat tires or a skewed front derailleur from down the street.

After immigrating to the U.S. in 1979, De Leon began fixing bikes out of his van in a nearby Washington Heights park. He got a job sanitizing medical instruments at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital for more than three decades, but he never stopped tinkering with bikes. He opened his business in 1994, before retiring from his hospital job in 2015.

The shop’s walls are cluttered with hanging bikes for sale, as well as parts and memorabilia, including De Leon’s 2011 certificate in sterile processing for hospitals, along with a photo of him with a former Dominican president a few years ago. Through a path between tires and boxes, De Leon places bikes on a stand in the middle of the store. Then, he takes apart the ones that need fixing, replaces parts, and puts them all back together.

Eventually, De Leon predicted, many New Yorkers will return to public transit. He’s not worried, though. He thinks New Yorkers, especially delivery workers, will still need his services, so he has no plans of putting away his tools anytime soon.

“I don’t want to retire and stay in the house,” he said, as he prepared to fix the next bike. — Eduardo Cuevas

Snapshot: NYC Covid-19 Cases, Hospitalizations & Deaths

The Doctors

The Doctors

What fresh med school grads learned on the front lines of the war against COVID

“We were all sort of feeling a little bit of hopelessness.”

![]()

Most of her life, Dr. Hailey McInerney has received comments on her big smile—one she often dons, a smile that has largely shaped her identity. Yet, throughout the last nine months of her residency, not even the nurses who work with her every day have caught a glimpse of it. Masked upon arriving to and leaving from their jobs at Mount Sinai West, how could they?

McInerney, 29, is a first-year OB-GYN resident. Last spring, when COVID halted working life as everyone knew it, it did the opposite for McInerney, who was set to graduate from the Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook in late May. In normal times, graduates would take a break, then begin their medical careers the way they had trained for them. But she graduated six weeks ahead of schedule and was called to the front lines to join the fight against COVID, as the need for medical professionals in hospitals throughout the country—and New York City, especially—surged.

After the Grossman School of Medicine at New York University became the first American institution to allow its students to graduate early in an effort to drive them to the front lines, 12 other medical schools in the state followed. The Renaissance School of Medicine was one of them, hosting its virtual ceremony on April 8, 2020. A few days later, she and her classmates walked into Stony Brook University Hospital as physicians-in-training.

It wasn’t easy. “We were all sort of feeling a little bit of hopelessness,” McInerney said.

McInerney didn’t have much time to wallow in the feeling. She and dozens of other young medical graduates had to jump into the battle against COVID without thinking about it. The trial by fire left impressions that will follow them throughout their lives and medical careers. And now, as the pandemic in New York starts to subside, they are starting to venture back into practicing the kind of medicine they expected to be doing after graduation—and pondering the lessons they learned.

“I think we’re more conscientious of infectious disease.”

The experience treating COVID patients ‘“reminded us of how we need to be human with our patients, and see them not just as a patient, but as another human being,” said AJ Schramm, a classmate of McInerney’s, who also joined the ranks at Stony Brook University Hospital.

The positions McInerney and Schramm were assigned called for them, essentially, to act as general medicine interns. This meant being placed on non-educational teams, rounding on a few patients a day, and helping out however they could. But rounds, which would normally entail a doctor physically checking in on a patient, looked different in a pandemic-ridden hospital. Rather than stepping into a patient’s room and spending 10-15 minutes examining them, doctors would poke their heads through the door, ensure the patient was holding up, and call them over the phone.

They made many other phone calls, meanwhile, to family members, to provide updates. For McInerney, this brought home the realization of how difficult it was to practice medicine without a family present, she said. It was one of many considerable changes she noticed. She had spent her medical school career watching family members accompany most patients at their bedside.

Without family, it became a challenge to communicate with many of the older patients, especially those whose native language is not English. Recently, in the emergency room, McInerney recalled treating a patient in her 90s, who did not know why she was in the hospital. “In a usual time, she would have people there with her who could really give me a better story of what’s going on,” McInerney said. “And I could take care of her better, truly.”

Being in obstetrics, though, she considers herself and patients lucky, as delivering mothers are permitted to have their partners with them during labor and delivery. It’s the only part of the hospital where this is allowed. But other than that, the soon-to-be mothers must still comply with the hospital’s COVID precautions, which include being tested upon entering, and wearing a mask, even during labor.

“We treat them as a sick person, until we get their COVID test back,” McInerney said of patients who come in during their final stages of pregnancy. “Then we say, ‘okay, they don’t have it,’ but everyone is a person under investigation until proven otherwise.”

Those who do test positive—fewer these days than back in the beginning of the pandemic at Mount Sinai West—are faced with difficult decisions moments after their babies are born.

If mothers test positive for COVID, “we don’t take the baby away from them, but we encourage them to not kiss their baby, which is the most horrible thing you can imagine,” McInerney said. They are also encouraged to keep their masks on while breastfeeding and have their babies sleep in small incubators, called isolettes.

McInerney, meanwhile, was unable to embrace her own mother before they were both vaccinated. Although they would see one another, it would always be masked and outdoors. Her mother, who she considers her best friend, was supposed to “hood” her during the graduation ceremony, a ritual that consists of a parent with some sort of doctorate degree—in McInerney’s mother’s case, a veterinarian—placing the hood on the shoulders of the graduate as they walk across the stage.

“It’s something you think about, your med school graduation, the moment you get accepted,” McInerney said. But with a virtual ceremony, it couldn’t happen.

Despite feeling sad about a ceremony that wasn’t, McInerney is now venturing into practicing medicine the way she expected at Mount Sinai West, where she has been working since last summer. Since then, she has delivered around 130 babies, and recently started doing C-section deliveries, as she is in the second half of her first residency year.

“We don’t talk about COVID that much anymore at work,’’ she said, ‘’which is refreshing.”

***

Schramm was also struck by the loneliness of patients in the era of COVID, and though he’d spent the last four years training at this hospital, he said he felt like an imposter.

“Even though the hospital felt familiar, and the topics we were discussing in the patients we were treating were all familiar to us, the role was all very different,” Schramm said. “And so I think it was particularly challenging to kind of take on those roles as physicians for the first time, in a time where help was spread thin.”

Being familiar with a space does not guarantee familiarity with what’s happening within it, Schramm, 27, soon learned.

“Usually, when you get a diagnosis, you know exactly what the treatment is, and you have experts in the field to consult, and you have a plan for that patient,” he said. “With the coronavirus, everything was still trying to be figured out.” Schramm compared it to a roller coaster—one day he’d know a patient was stable, while the next day he wasn’t sure at all.

But a constant, throughout, was the steep learning curve. Not only were he and his recently graduated classmates actively learning about this illness that they had never heard about before, but they were witnessing specialists, like dermatologists and gastroenterologists, who’d spent their entire careers focusing on specific issues, return to the basics.

“Seeing that they retained all of their fundamental skills in medicine was an inspiring thing,” he said. It showed Schramm that no matter how specialized a practitioner he’d one day become, the skills he was learning then were ones he’d always be able to turn back to. It also taught him that, in medicine, there will always be more to learn.

Like McInerney, Schramm also served as a lifeline to the outer world for his patients. At a time when no family members were permitted to see their sick relatives, Schramm felt responsible for maintaining a personal connection with the ill. For him, getting to know the lives, families, and interests of those he was treating became one of the most meaningful parts of his time there.

These days, Schramm is a first-year resident at the Columbia University Department of Anesthesiology. While he has great hope in vaccinations, he does not think the world will be the same, in terms of normalcy, after COVID.

“I don’t mean that to be in a negative way,” Schramm explained. “I think that could be a positive. I think we’re more conscientious of infectious disease, just how vulnerable our health system is, and protecting yourselves and making sure that you stay healthy.”

***

Like Schramm, Matan Uriel, a first-year resident at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in the Internal Medicine Program, said he also felt unprepared as he stepped onto the front lines to help treat COVID patients.

He had arrived in the United States from Israel last June to begin the residency, after having spent a year teaching at a pre-med school back in Israel before it shut down due to the pandemic. Prior to the closure, students at the school he worked at were taught the basics in chemistry, biology, anatomy, and physiology and were well versed on how to get accepted into medical school. Uriel taught for roughly a year, after graduating from Semmelweis University of Medicine in Budapest, Hungary.

But, as Schramm noted, it seemed as if no amount of training could have prepared him, or anyone really, for working within hospitals besieged with COVID patients. Though Uriel, 32, would know exactly what needed to be done, many times, it wasn’t enough.

“I know what our option is medication-wise, and supplemental oxygen-wise, and I know I can give it to them,” Uriel said. “But a lot of them will continue to deteriorate. And if they’re that sick, sometimes you feel hopeless as a medical professional.”

Yet, his COVID-19 patients ended up being the ones he has felt the closest connections with, thus far. He’s not exactly sure why, but suspects it could be connected to the fact that, with these patients, his resources were more limited than they may have been with patients dealing with different issues.

“Starting in the heat of the pandemic, and knowing how sick they were, maybe made a difference as well,” he said.

And despite the layers of personal protective equipment he’s had to dress in, Uriel still feels he was able to establish and maintain connections with his patients. He’s unsure, though, if the patients felt the same way—that there were not any communicative or emotional barriers.

“You wear all that, and you look like you’re on Mars,” he said. “But, basically, you still connected with the patient, and you still feel the patients, and they still see you as their doctor.”

Uriel emphasized the importance of remembering to live life during this time—especially as a healthcare worker. For him, this meant making time to do the simple things: work out, watch some television, and spend time with loved ones. “So when you go back’’ to the hospital, he said, “you have that ground to stand upon.” — Jasmine Fernández

NYC Covid-19 Total Cases, Hospitalizations & Deaths by Age

The Addiction Physician

The Addiction Physician

A physician that specializes in addiction medicine hopes treatment will be as accessible as it was during the pandemic

“We were in a circumstance where I needed to treat a patient and do the best I could with what I could.”

![]()

Last year, Stefan Kantrowitz, an addiction medicine physician located in Midtown East, said he thinks he might’ve broken protocol.

When the pandemic hit and a patient needed medication, he prescribed it over the phone without thinking twice. Kantrowitz, 34, treats people who struggle with substance use disorders, HIV, and Hepatitis C.

“I did something before, technically, I should have,” Kantrowitz said. “We were in a circumstance where I needed to treat a patient and do the best I could with what I could.”

On March 16, 2020, his actions became acceptable. Then, doctors in the United States were permitted to prescribe controlled substances for patients whom they have not evaluated in person. Without this option, Kantrowitz said, “people would have been left to their own devices.”

Stefan Kantrowitz

With the lockdown, many with addiction and mental health issues suffered even more. In 2020, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Helpline received 833,598 calls nationwide. This is a 27% increase from 2019. Even more dire, ABC7 reported last month that New York City saw a 21% increase in overdose deaths since March of 2020.

Without the ability to treat people on the phone and online, Kantrowitz said, the pandemic and substance use disorders would’ve claimed even more lives since last year. If anything, more accessible care made it easier for many who really needed help.

The pandemic was “a new existential threat on top of existing problems,” said Kantrowitz.

Kantrowitz can’t say exactly if he witnessed a spike in patients calling for his help during the pandemic. Patients’ insurance issues and unemployment problems made it almost impossible for him to keep track. But the city-wide statistics speak for themselves as to how people were seriously affected by the pandemic.

Kantrowitz said he knew he wanted to treat patients with substance abuse disorders when he was exposed to them in college. So pursued a fellowship in addiction medicine at the University of Buffalo from 2014 to 2015. Kantrowitz’s approach to healing is a holistic one that sometimes includes medication to reduce substance use.

Karowitz said he doesn’t lose sleep over work because he knows he does the best he can with the knowledge he has. But during the pandemic, he spent a lot of time wondering how his patients were doing. He thought about how their lives were altered and how they’d cope.

Even though people were stuck inside during the city’s shutdown, Kantrowitz said, people who struggle with substance use will usually find a way to use, regardless.

He pointed out that liquor stores were considered essential businesses that could remain open even during the height of the pandemic, and alcohol could be ordered with takeout food from restaurants and bars– making it even harder for people to avoid their vices.

Many of Kantrowitz’s patients come from disadvantaged backgrounds. So on top of being marginalized for their addiction, they had trouble financially. Then, he said, the pandemic made it even more difficult to properly treat them. He called this combination “the trifecta of disaster.”

But Kantrowitz said there is a silver lining for addiction treatment during the coronavirus: care became easier to access by those who need it. In addition to doctors being able to prescribe drugs remotely, some methadone clinics were even delivering the life-sustaining narcotic to patients’ homes, he said.

“Now, the question is, how do we keep this going?” Kantrowitz said. “How do we actually use this to provide more equity and make it a permanent thing?” — Jayna Alexandra

NYC Covid-19 Total Cases, Hospitalizations & Deaths by Borough

The Fitness Entrepreneur

The Fitness Entrepreneur

Crowned the ‘Resilient Queen’, this businesswoman is back stronger than ever

“Dancing is truly special to do with people in the room.”

![]()

Sadie Kurzban couldn’t contain her excitement. Immediately upon landing in New York City after her flight from Miami on Monday, May 10, the owner of 305 Fitness didn’t go to her apartment. Instead, she went straight to her Upper East Side dance studio, which had been closed since March 2020.

And on the day of its grand reopening, Kurzban, 31, picked up right where she, and other fitness enthusiasts, left off—dancing to a live DJ under the bright pink strobe lights shining in the overhead disco ball.

After a 14-month hiatus, Kuzban’s slice of Miami in Manhattan welcomed masked dancers back to sold out classes at two of its Manhattan studios. One fitness enthusiast posted on Instagram: “Best Monday in 14 months.” Another wrote, referring to the 305 Fitness studio: “She’s back and she’s stunning. Feels good to be home.”

Kurzban herself wrote that she was “grateful” and “overjoyed,” and was crowned “resilient queen” by her followers.

It’s a fitting coronation for Kurzban who, during the pandemic, had to pivot her dance fitness studio empire with locations in New York, Boston, and Washington D.C. from holding classes in person to building a digital presence. Somehow, she’s emerged stronger than ever. During the shutdowns, she offered continuous support to the fitness community she built from the ground up over the last decade and even came up with some new ways to grow her business to the next level.

“The values that 305 Fitness has been espousing for a long time: joy, self love, and community, all of these things are so needed right now,” Kurzban said.

The studios’ reopening also represents a coming home for Kurzban, too, who has been living in Miami since the start of the pandemic. In March 2020, she was on a trip to visit her parents there when COVID-19 arrived and spread through New York City. Knowing how the pandemic was affecting China and Italy, she said she felt a moral obligation to close the 305 Fitness studios in the city on March 14, 2020, before the state issued mandates concerning gyms and fitness classes.

Kurzban immediately scoured the budget to find enough money to pay her instructors and staff a few weeks severance. As the closures continued, she instructed her employees through the often confusing process of filing for unemployment. Kurzban also gave the instructors the option of using the 305 Fitness branding, choreography and music to start their own online dance community.

“It became this way of being connected and not feeling so alone.”

Kurzban herself began hosting free 305 Fitness YouTube classes broadcasted from her parents’ backyard at 12 p.m. each day. In order to give it the feel of an actual studio, she painted an exterior wall bright pink. Anywhere from 500 to 1,000 dancers from across the country would tune in and break a sweat with Kurzban.

“It became this way of being connected and not feeling so alone,” Kurzban said. “We were doing it together.”

Later in the pandemic, Kurzban focused on other ways to spread dance to those stuck at home. She launched the 305 Fitness on demand library, featuring digital workouts that dancers could do from anywhere on their own time, and she focused on certifying more instructors. Charging just $39 a month, the certification allows instructors to “monetize their passion,” according to Kurzban, by making upwards of thousands of dollars a month teaching online, outdoors, or at a studio.

Although Kurzban will call New York her home again next month, she spent time in the city mid-May to take “as much class as possible” and witness her studios come back to life. She also welcomed back 90% of the same staff 305 Fitness had employed back in March 2020. Kurzban said this retention post pandemic is unprecedented in the fitness industry and among her competitors.

Kurzban said she’s thrilled for “305 to just pop again.” She is proud of the community she’s grown virtually over the last 14 months, but she admits there’s nothing like being in-person with her fellow dancers under the glow of a glittering disco ball— moving to the sound of the DJ’s familiar beats.

“Dancing is truly special to do with people in the room,” Kurzban said. — Kate Christobek

NYC Covid-19 Total Cases, Hospitalizations & Deaths by Poverty Levels

The Foreman

The Foreman

A construction worker helping New York City return, one roof at a time

“When you have a roof ripped off, you can’t just leave it for four months.”

![]()

Last spring, Mike Caldwell was working on restoring Manhattan’s historic Roosevelt Hotel on East 45th Street—one the city has known since 1924. Little did he know, the roof he was renovating would soon be covering the heads of healthcare workers seeking shelter as COVID-19 struck New York City.

Caldwell, 59, is a roofing foreman for Nicholson & Galloway, the country’s oldest restoration company, founded in 1849. It specializes in the exterior restoration of masonry, roofing, and sheet metal, according to its site. He’s been there for 18 years. Every day, he takes a train from Hauppauge—the Long Island hamlet he calls home—to New York City, where, what to us is a roof, to him is a workspace.

But when New York City went into full lockdown because of the pandemic, so did Caldwell—for three months. He says he had enough money set aside to sustain himself, so he used the time to take a much needed break. It’s hard work, after all, Caldwell said. And his broad, callused hands affirmed it.

At the beginning of June, it was time to return and complete his job at the Roosevelt. Yet the subways and trains Caldwell has spent 35 years commuting on would have suggested otherwise. “These trains are constantly packed like sardines,” Caldwell said. But now, for the first time, they were empty. “It was awesome.”

Although Caldwell and his colleagues may not initially have been considered essential workers, their projects certainly were. “When you have a roof ripped off, you can’t just leave it for four months,” Caldwell said.

After about a week, his work at the Roosevelt was done. And soon, the hotel became one of the many New York City establishments to provide special housing rates for first responders, who were potentially contagious. But just a few months later, in December, the hotel’s doors permanently shut because of a drastic loss of revenue induced by the pandemic.

“You’ve got to work hand-in-hand with the men, you don’t work alone.”

His next project became Columbia University’s Lerner Hall, where he is still replacing a complicated roof system, with 13 other men—a number that varies depending on what’s being done. Now, though, he says it’s become a challenge to get workers, especially young apprentices, to come in. Caldwell suspects they are receiving more income from unemployment checks than from working.

Working during a pandemic was different. He remembers the first time he and his buddies saw their coworker, a man named Freddie, in COVID-protective gear. “We would goof on him,” Caldwell said. “He would be the only person on the subway with a mask on and gloves on.”

But it was no longer a joke when masks became the norm, along with other safety regulations, such as hand and eye washing stations, a doubled amount of paperwork for projects, and daily temperature checks. If they didn’t follow the rules, they ran the risk of getting charged a $5,000 fine from Department of Building inspectors, who would frequently visit and check in on construction sites, and still do, Senior Project Manager Steven Savva said.

As construction workers, maintaining six feet of distance proved to be difficult, too.“It’s almost impossible,” Caldwell said. “You’ve got to work hand-in-hand with the men, you don’t work alone … and you’re lifting heavy stuff.”

Usually, Caldwell has 16 to 20 men on his crew, but now he separates them into groups of four or five while working. Though he couldn’t speak for what his crew members were doing in their spare time, Caldwell knew the only other person he’d been interacting with during the pandemic was his daughter—an ESL teacher who’d been working from home.

He didn’t remove his hard hat, mask, or prescription glasses—dimmed, once in the sunlight—but as he spoke about the possibility of life and work returning to normal, his warm smile beamed right through. — Jasmine Fernández

Tooltip Text

NYC Covid-19 Total Cases, Hospitalizations & Deaths by Race

THE BROKER

The BROKER

Manhattan commercial real estate brokers see signs of recovery as workers eye a return to the office

“This month, in the past couple weeks, I’ve seen significant changes in the city.”

![]()

Jonathan Anapol, was on his way uptown from his Midtown Manhattan office to meet a client in early May when he came to a stop on 6th Avenue. “What the heck’s going on here?” he said he asked the driver. Anapol was stuck in traffic.

Anapol has been in the city since 1980. This certainly was not his first traffic jam. But over the past year, he said gridlock had become an anomaly in a once-bustling city.

Still, If there is anyone who could take delight in a Manhattan traffic jam nowadays, it’s Anapol. He is president of Prime Manhattan Realty, a commercial real estate brokerage he founded in 1994 and grew to a team of about 20 brokers. As president of a brokerage in one of the commercial real markets hit hardest by the pandemic, Anapol is most eager for any portent that the downturn might be beginning to end. Traffic jams? Bring them on.

“I definitely took it as a sign of a return for sure,” he said. “A little bit of back to normal.”

The pandemic has been rough on the commercial real estate market. Anapol said he had made it through several downturns in his career. He was a broker through the dot-com bust, 9/11, and the 2008 recession. “Putting aside the tragedy of 9/11, this was more impactful to the city than anything,” he said.

Anapol still retains a hint of his Massachusetts accent from his upbringing near Cape Cod. He has been an entrepreneur his entire working life – first in the apparel business before being introduced to real estate by a friend – and speaks about the events of the past year in the even-keeled tone one could expect only from someone who has weathered a choppy market before.

He said business dried up right away at the beginning of the pandemic in March of 2020. The majority of the calls he received were from clients asking about whether they needed to pay rent. He and his staff leaned heavily on lawyers to scour their clients’ leases and look for any advice they could offer.

“Landlords with a lot of small tenants, they’ve been hit hard.”

“We were helping people sort out the process,” he said. “We were customer service with our clients trying to, you know, hold people’s hand and advise them.”

The market remained in a standstill from April of 2020 until around July or August, he said, and he began going into the office a few days a week.

Manhattan office vacancies reached 16.3% as of the first quarter of this year, according to a recent Cushman & Wakefield study, up from 11.3% in the first quarter of 2020. The historical average vacancy is 9.8%. Furthermore, new office leases were down in Manhattan by more than 38% year over year.

“Landlords with a lot of small tenants, they’ve been hit hard,” said Alan Rosinsky, principal broker at Metro Manhattan Office Space. “And it’s, you know, it’s small landlords. Landlords with side street buildings. Landlords that have divided their floors into a lot of small units and many of the smaller units have disappeared.”

With the rise in vacancies and the uncertainty about demand in the near-term, some experts, including the New York City Comptroller’s office, see potential for sustained downward pressure on commercial rent prices – potentially hitting the bottom line of commercial real estate landlords for years to come.

But, like the traffic jam on 6th Avenue, there are signs that recovery may be around the corner.

On May 3, close to 80,000 municipal employees began returning to the office after more than a year of tele-working. Major private sector employers have also signaled their intent to bring workers back. In late April, Bloomberg reported that JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon, in an internal memo to employees, said he expected the bank’s U.S.-based staff to return to the office on a rotational basis by early July.

A return to work in-person, of course, will likely be an important catalyst to the city’s recovery. More workers back in the office mean more riders back on the subway and more patrons at lunch spots and happy hours and many other stores and venues in hard-hit retail corridors surrounding business districts.

It is still unclear if occupancy will return to pre-pandemic levels. In his letter to shareholders, Dimon, said 10% of JPMorgan employees may work from home indefinitely and that the company may need up to 40% less desk space going forward. Rosinsky said he represented a client that recently downsized from a 6,000-square-foot space to 3,200-square-foot space.

But Rosinsky and Anapol both remain optimistic. They say there is recent movement in the market and both of them have clients looking for new space in Manhattan. Anapol thinks as more employees return, like the 80,000 city workers, it will continue to snowball. And with rents at bargain rates, both see opportunities for smaller companies to move to office space they may not have been able to afford previously.

“I think the city’s going to rebound very nicely,” Anapol said. “You know, I mean, this month, in the past couple weeks, I’ve seen significant changes in the city.” Including a lovely traffic jam. — Joseph Clark

NYC Covid-19 Total Cases, Hospitalizations & Deaths by Sex

The Community Composter

The Community Composter

Curbside compost pickup is returning, but there is still work to do

“If we want to see something happen in communities and we want the world to be a certain way then, we just have to go out there and create it.”

![]()

When Clay Burch goes to Cooper Park in East Williamsburg, Brooklyn, most people recognize him. He is the guy who, since July 2020, stands at the west entrance of the park every Sunday with the 27-gallon bins full of rotting food.

Every week since then, Burch, 33, and his small compost operation called Brooklyn Scrap Shuttle collects compost at a local community park. The group fills a void left by the city when it decided last April to cancel the Brown Bin program, a door to door compost pickup, until June of 2022, due to pandemic related cost-cutting measures. But on April 22, the city reversed itself and announced that it would start up the program again. With Brown Bins returning to Burch’s community in October as the city reopens, he has mixed emotions: He’s glad the program is returning, but he is also sad that he will no longer see his community every week. When he stepped up to help, Burch grew to love the work. It led to new friendships and gave him a sense of purpose.

“If I were to stop doing it in my neighborhood, I would kind of hate that, not seeing all the people that I’ve seen for the past year,” he said, lamenting the possibility of losing the connection to his community. “It is what it is.”

The city’s decision on April 22 to reinstate curbside pickup came as a surprise to Burch, who was not expecting the service to return for several years. In Burch’s view, the suspension last year was a major setback to the city’s environmental health, so he decided to take up the issue himself and founded his own community-based composting operation. “There’s 8 million people here and we create a lot of waste,” he said. But when the service resumes, it will return to its past inadequate form, he says.

Burch had criticisms of the Brown Bin program prior to the pandemic. The program was only offered in certain neighborhoods due to lack of demand in certain zip codes, according to the city government. Many communities of color are also left out of the service, as a result. “It will be basically the same as it was before. It wasn’t serving everyone in the city,” he said.

In order to make a difference, Burch, a gymnastics instructor and freelance photographer, had a lot to learn when he started the Brooklyn Scrap Shuttle. “I was super nervous,” he said. “Stepping outside of your comfort zone is a little nerve wracking at times but it paid off.” “I was super nervous,” he said. “Stepping outside of your comfort zone is a little nerve wracking at times but it paid off.”

As weeks of composting turned into months, Burch developed a routine. He found partner organizations to send food scraps for processing, and he secured an electric bicycle to transport his 27-gallon bins. He even grew the operation to include a dozen volunteers.

Between 11 a.m. and 3 p.m. every Sunday, Burch collects food scraps, filling up to eight bins a day, averaging a total of 560 pounds a week. Then, he transports them from Cooper Park to a Department of Environmental Protection composting site just two miles away, using a bicycle with a cargo trolley tethered to the back. Because of the weight, he makes several trips a day.

To accumulate 560 pounds of compost, over 70 people visit Burch to drop off their weekly food scraps. For many families and park goers, visiting Burch has become part of their Sunday routine, whether it’s stopping by on their way to weekend errands or on their way to an afternoon in the park. Parents make it an outing for their children to dump food scraps into bins, and dogs are overcome by curiosity with the decomposing smell. To some, composting’s faint, decomposing scent is putrefying, while for others it’s freshening, a sign that nature’s regenerative process is beginning.

For longtime composters like Joann Lee, Brooklyn Scrap Shuttle has been a relief, despite the odor. “It was really weird to throw our food scraps in the trash for the first few weeks because we really built this habit of being able to compost,” said Lee. Now she drops off her food scraps every week while walking her dog. “I remember when he first started doing this on his own, it was just him and his bike,” she said. “It was really amazing to see how big this whole operation became.”

The strength of his community to take matters that are important to them into their own hands surprised Burch. “It’s been really amazing to see people come together to do this work,” he said. But with curbside pickup returning in the fall, Burch knows his time in Cooper Park is coming to an end.

Burch plans to continue his work, even if it’s not in East Brooklyn. Now that he knows what to do, Burch wants to bring his compost model to other communities that don’t have the Brown Bin service. Seeing the impact Brooklyn Scrap Shuttle has had, Burch believes in the power of individuals and of the community to achieve its goals. “We are powerful creators,” he said. “If we want to see something happen in communities and we want the world to be a certain way then, we just have to go out there and create it.” — Seiji Yamashita

Snapshot: NYC Positive Covid-19 Tests

The Wedding Photographer

The Wedding Photographer

COVID-19 nuptials through a Brooklyn lens

“Their day is just as important to me as it is to them, and I’m here for them no matter what.”

![]()

Hilary Katzen has been known as “the photographer” since she was in high school in Florida. When Katzen’s friends started getting married a decade after they graduated and went their separate ways, they all wanted her to document their big day. And she did, traveling to New York, New Jersey, California, Virginia, and North Carolina to fulfill their wishes.

Wedding photography became Katzen’s expertise and for the last five years, it’s been her full time job. Now, she works out of her home in the East Williamsburg neighborhood of Brooklyn. But with the pandemic, strict health guidelines prevented people from leaving their homes— let alone hosting events like weddings. So, venues closed their doors, couples changed their dates, and wedding photographers like Katzen kept their lens caps on.

Lucky for Katzen, she didn’t have to cancel any of her booked weddings because of the pandemic. All of her clients– about 15 of them– whose dates were set during the shutdown, were able to reschedule their special day with Katzen. And to help the couples out during a stressful time, she didn’t issue any rescheduling fees.

During the worst of the pandemic, Katzen said she was worried about her livelihood. How could she not be? But she kept her cool, she said, and tried to ease her customer’s stress and anxiety about the unknown.

“We got this, we’re in this together,” she said she’d tell clients. “Their day is just as important to me as it is to them, and I’m here for them no matter what.

Wedding bells are ringing again– and Katzen is in demand again. Right now in New York City, wedding ceremonies can fill 50% of a venue, with a maximum occupancy of 150 people. This is the largest wedding guest list allowance since March 2020. To work around her client’s rescheduled 2020 dates, Katzen took on only about 50% of her typical wedding client count for 2021. She’ll photograph fewer weddings this year than her usual 30, “because life is short,” she said.

“We still celebrate love, we still celebrate life.”

She’s now figuring out how to adjust to this new normal. Even with these more lax health guidelines, wedding photographers, like Katzen, face new obstacles that bar their creativity. “I really thrive off candid photography,” Katzen said, trying to explain how things are different now. Before the pandemic, she loved capturing “raw, nostalgic emotion that can be seen without gestures, and just body language.”

“Now, there’s a mask,” she said, making it impossible to capture natural smiles.

On the other hand, Katzen has been able to capture moments she’d never imagined, like when she shot a “cute little ceremony” near the Brooklyn Bridge. An iPhone on a tripod had a front row seat to a microwedding with just the couple, the officiant, and Katzen in attendance. The bride and groom wore AirPods in their ears so that their voices could be heard from Japan, Mexico, and Australia, where family members watched them tie the knot on their screens.

The pandemic has taught Katzen to be flexible. Regardless of the venue and guest list, her main goal always is to encapsulate the spirit of a wedding for her clients.

“I want this day to go as beautiful as you envisioned it, whether there’s a pandemic happening or not,” Katzen said. “We still celebrate love, we still celebrate life. And we still have these moments. And these are the moments that we live for.” — Jayna Alexandra

NYC Covid-19 Total Positive Antibody Tests

The Nail Salon Owner

The Nail Salon Owner

Long overshadowed by other service industries, salons are finally feeling some hope

“Even pre-COVID, we were big on hygiene and sanitation.”

![]()

On April 30th, Governor Andrew Cuomo announced that indoor dining could increase to 75% capacity on May 7, and with it, almost as an afterthought, he included personal care services, such as nail salons. Sunny Moon, owner of Spa Bene, a salon on the Upper West Side, was paying attention.

“Lot of state and city government, they talking about the restaurants,” said Moon, “but they never talk about our business.”

Moon opened Spa Bene in 2015, and has owned (and sold) 10 nail salons ever since she emigrated from South Korea to the United States in 1985 at 28 years old.

Now 63, Moon uses one of Spa Bene’s manicure stations as an impromptu office, with a complex datebook to organize appointments for customers, many of whom she knows by name. And her familiarity with clientele doesn’t stop there: customers will even leave their coats and bags with Moon while they run errands before their scheduled appointments.

In addition to Moon’s hospitality, it’s no wonder her customers are so loyal: Her Spa Bene is spacious and flooded with natural light. Moon offers outdoor manicure, pedicure, and even massage services on the location’s impressive backyard deck.

Moon’s small stature is no match for her powerhouse disposition, even though she describes herself as shy. After so many years in the industry, her business sense seems almost innate. She’s kind and matter of fact, and her eyes are always darting around the salon to make sure that all her customers are taken care of.

She closed the salon in advance of the citywide shutdown mid-March 2020—to protect her employees, she said, because one of them had caught COVID. She retreated to New Jersey, where she lives, for four months, and then reopened in July of 2020, having downsized from 27 to 17 employees.

In a tumultuous year, nail salons in particular have struggled, as they are businesses not widely viewed as essential, and owners say they have felt passed over by state and city aid measures. They have survived by going to bat for staff—by staying open, paying employees out of pocket, and helping them apply for federal and state funding— time and again, but their personal finances and their landlords’ support is dwindling as New York enters its fifteenth month of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Thanks to Cuomo’s recent announcement that personal care salons can expand to 75% capacity, salon owners hope that they will finally begin to see some improvements to their bottom lines after a difficult year.

“I think city gonna get better, time goes,” said Moon. “But I don’t know when.”

Like most other small businesses in the city, nails salons have taken a major hit during the pandemic. Jason Zhang, owner of Beauty Cutie in Noho, said his business is down 65 to 75 percent. Spa Bene reported similar numbers. “We only make 30% compare to 2019,” said Moon, talking about the salon’s January/February numbers in 2021.

A big part of nail salon income in many cases depends on foot traffic, which has a lot to do with the success of walk-in salons like Spa Bene, Beauty Cutie, and Above Pigment, in Tribeca. Zhang said without the business of nearby hubs like NYU and bustling Union Square office buildings, business is incredibly slow.

“I don’t have any choice but to keep pushing and pushing and pushing.”

Similarly, Jason Zheng, owner of Above Pigment, awaits the re-opening of the Borough of Manhattan Community College, across the street from his salon.

To make up for the revenue lost from decreased foot traffic and mandatory closures between March and July of 2020, salons applied for Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans from the Small Business Association. In accordance with guidelines from the Small Business Association, Jason Zheng, Jason Zhang, and Sunny Moon all said they used 60% of the PPP loans they received to pay employees salaries and the other 40% toward their rent.

However, Zhang says he found the loans he received to be insufficient for the pricey location in which his business is located. “My store? The rent is higher, very higher. Ten thousand dollars a month,” he said. Moon says she had a similar experience, explaining that her rent is so high that the first PPP loan she received only made a dent in it.

Moon’s experience with federal loans wasn’t easy, either. Although she employs more than 10 staff members, she was told that she was ineligible for a grant because Spa Bene is located in an affluent area on the Upper West Side. That didn’t make much sense to her. “I’m not rich, I don’t fit in the rich area,” said Moon. “Why I cannot get it?” She is also frustrated that many restaurants and bars received grants while she was passed over.

But help came from elsewhere for Moon: she has a generous landlord who gave her discounts on rent and has been understanding that she can only pay bills “little by little.” When explaining her gratitude toward her landlord, she stressed that help is needed at all levels: “He have to pay the mortgage,” said Moon. “He needs support, too.”

Moon says she has done her best to support her staff, meanwhile. Even though her business is slow, she says she has made a point to stay open to keep her staff employed. To manage, Moon dipped into her retirement savings—more than $70,000, said Moon—“because we didn’t have any income.” She had employees reduce their hours throughout the pandemic at the salon in order to avoid layoffs. “I don’t have any choice but to keep pushing and pushing and pushing.”

Like other businesses in the service industry, nail salons had to purchase their own personal protective equipment and cleaning supplies, adding expenses to stretched budgets. Prices for staple cleaning products, meanwhile, such as gloves and disinfectants, have more than doubled as businesses from all sectors of the service industry scrambled to keep their employees safe. Moon recalled her shock at the massive price hike for one case of disposable gloves: “Before, we buy about $6. Now? Cheapest one I get is $16.”

So, to make ends meet, many owners and their partners have gotten creative. Lori Sardoff, the founder of Snailz, a booking app that allows salon customers to schedule and pay online, reached out to manufacturers to create lucite dividers for her partner salons before realizing that the state would even require it. “I literally went to the people that created the furniture for my daughter’s Bat mitzvah, because I knew that they must be sitting with all this crazy plastic inventory,” said Sardoff, whose partner salons include Beauty Cutie and Above Pigment.

By selling dividers at a discounted rate to make up for her own lost business, Sardoff maintained relationships with the clients that kept her above water as well. ”I can’t succeed if they fail. So it behooves me to make my salons successful,” she said.

In addition to the mandated dividers and capacity restrictions, the staff at some salons went above and beyond state requirements.

“Even pre-COVID, we were big on hygiene and sanitation,” said Manuela Beeck of Glosslab, a membership-based nail salon franchise that has locations across the city, whose new policy requires their customers to sanitize their cell phones if they want to use them during an appointment. “It’s shocking to me how few places require you to clean your phone.”

Glosslab also stopped simultaneous manicures and pedicures, “because it would mean that the technicians were too close.”

Nail salon workers were not prioritized in New York’s initial vaccine rollout, despite being in a high contact line of work. As vaccine eligibility gradually increased throughout the spring, beauty and personal care technicians had to wait until they personally met other criteria to qualify.

Now that the state has opened up appointments to everyone 16 and older, salon owners are left to their own devices to decide whether or not they’ll require their employees to get vaccinated. Many have taken a hands-off approach and not required their staff to get the vaccine, but recognize that their customers might feel safer knowing their employees were immunized.

Despite their frustration, salon owners say they are cautiously optimistic about the future. As restrictions are lifted and more foot traffic allows for more walk-ins, some owners have seen appointments increase.

“Customers definitely will be feeling much safer,” said Zheng. “People starting coming back.” — Patricia Crimmins and Madeline Renbarger

NYC Covid-19 Total Positive Antibody Tests by Age

The Florist

The Florist

A flower arranger decorates her way out of the pandemic

“Working with flowers is pretty much the happiest you can ever get.”

![]()

Mira Lee, who has been a florist for almost nine years, found herself on the edge during the pandemic. Weddings abruptly ended, and funeral flower decorations were no longer needed. Flowers were not a priority.

But eventually, Lee found a way to stay creative and solvent: She was commissioned by Samwon Garden, a popular Korean BBQ joint in Manhattan, for major installation projects. That has renewed her hopes of restoring her business in the new season, and has given her something to look forward to.

The year 2020 was “ really hard on everybody,” said Lee. “But now, in 2021, a lot of things have changed, and people are getting vaccinated.’”

In early May, Lee had just wrapped up her latest projects for the restaurant, on West 32nd Street: a beautiful blooming archway filled with spring bouquets, a floral tunnel leading to the restaurant’s mezzanine, and an enchanting lavender wisteria hanging from the ceiling of the top floor, evoking a true secret garden tucked away in New York City.

“We used all the different kinds of flowers from delphinium, peonies, roses, and greens,” Lee said. “You name it, we have it down there.”

This had been one of the biggest installations she’s taken on for the store, Sylvan Grace in Leonia, New Jersey, which had been a popular floral shop for the Korean community both in New Jersey and New York. She had been working there since the start of her floral career, and became a co-partner about five years ago.

About 4,500 silk flowers and greens went into building the three projects for Samwon Garden. The restaurant wanted the flowers to symbolize a fresh start, evoking a brighter post-pandemic future. “They wanted to make something like spring,” said Lee. “They wanted to make a new start and make everybody happy.”

“They wanted to make a new start and make everybody happy.”

The flower industry could certainly use a new start. According to the latest annual report from IbisWorld, a global market and industry research firm, the coronavirus pandemic in 2020 generated the floral industry’s largest single-year revenue contraction in recent history. Lee’s store, too, suffered.

Sylvan Grace employed up to five florists and two delivery workers prior to the pandemic. During the pandemic, until the installation project, however, Lee was the only person working in and out of the store for the few orders remaining. In fact, she said, she lost approximately 80 percent of her business, and the store fell three months behind in rent this year.

The installation at Samwon Gardens helped out a lot, according to Lee. Now, the shop has been able to pay all the electricity bills, and orders are coming in. She said she is getting busier, meanwhile, as flower orders are picking up. Mother’s Day just passed, she noted, and Sylvan Grace still has orders to fill.

“Working with flowers is pretty much the happiest you can ever get,” said Lee. “You get to play with flowers, and you get to enjoy the flowers and most of all, when you deliver the flowers everybody’s so happy.” — Sarah Chung

NYC Covid-19 Total Positive Antibody Tests by Borough

The Production Assistant

The Production Assistant

New York’s vibrant film industry is bouncing back, and jobs on set are opening up again

“We tried to stay hopeful, and directors would have long calls with me predicting when they would restart.”

![]()

Originally, Kirill Gudkon wanted to be a doctor. But after graduating college, he took a leap of faith to pursue his passion for filmmaking instead. A naturally creative and witty person, he has an effortless command over the camera, thinking up beautiful shots on demand, and spending his time making short movies for fun.

In 2018, Gudkon, a 25-year-old immigrant from St. Petersburg, Russia, scoured social media– beginning his uphill journey to break into New York City’s vibrant, competitive, and hectic film industry.

“When I started out, I was just endlessly refreshing Facebook groups that were looking for production assistants for the day. If I got lucky, there would sometimes be a spot for a newbie to step in and take someone’s place,” said Gudkon.

He got his first gig as a production driver for just a single day on an independent film. Because he proved to be so resourceful, he ended up getting hired for the entire production. With time, Gudkon built a strong network of colleagues who referred him for more advanced jobs, and he is now well known among producers and filmmakers in the city’s independent film circle.

A production assistant just starting out can be tasked with anything from traveling 10 miles to buy a smoothie for an actor to loading up a truck full of equipment. As they move up the ranks, their responsibilities can evolve to being included in creative decision making, assisting with the shoot, and giving production input.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, however, the $60 billion film industry in New York City came to a screeching halt – as did Gudkon’s career.

Similarly, hundreds of contract workers and freelancers – professions already known for their instability – lost their jobs. On average, about 1,000 permits per month were given to small-scale film productions in the city in 2019, but last year, they averaged less than 500 a month. For Gudkon, that meant months of sitting around without work.

Gudkon said when the pandemic forced all projects to shut down immediately and indefinitely, nobody knew how long it would last.

“We tried to stay hopeful, and directors would have long calls with me predicting when they would restart,” Gudkon said. “But their prophecies varied so much. I just figured they had no idea either and I had to just be patient and wait it out.”

Production assistants, or PAs as they are known in the trade, are no strangers to dry spells with few job opportunities, particularly in winter months. PAs expect that there will be little work due to the cold and holidays, and they plan accordingly. But this was different. Most films couldn’t be shot remotely, so projects that filmmakers were depending on for income had to be canceled or postponed. Fortunately, Gudkon worked constantly in the months leading up to the pandemic, leaving him with enough savings to weather the uncertainty.

Luckily for Gudkon and others in the industry, filmmaking is slowly returning to the city. By the end of July 2020, New York City began allowing “small-scale, outdoor productions” to take place. Film crews saw the light at the end of the tunnel, and Gudkon was one of the first to be back on the job.

“I remember feeling proud to be back to work on that first day, on a docuseries shoot in Harlem, excited and optimistic about the future for the first time in a while,” he said. “But the excitement was short-lived, because it was still a whole month before I got another gig.”

Shooting resumed in spurts as the industry figured out how to implement and enforce COVID-19 safety protocols, particularly on closed sets and small work areas. Calling it “uncharted territory,” Gudkon explained that in many cases it was impossible to ensure the protocols would be followed.

“Many productions had to downsize to be able to maintain social distancing. Everyone had to get tested for COVID-19 regularly, sometimes every 48 hours for a single project,” he said. New positions like “COVID Compliance Officers” were introduced – in some cases, entire teams were dedicated to it – to maintain mask and sanitization efforts, as well as keeping track of each crew member’s tests, quarantine requirements, and consequent shooting schedules and plans.

But as New York City’s vaccination rollout stabilizes, many workers, especially freelancers, in the entertainment industry are getting vaccinated so they can work on films again. “As a freelancer, you know that your wellbeing is the only thing that actually provides you with job security,” Gudkon said. “If you get COVID and can’t work, you’ll be the one out of a job. They’ll simply find a replacement.”

When the industry went back to normal, Gudkon was relieved to make money again. But he was mostly excited just to be back in the field he adored.

“Once we reopened, I buried myself in work because the lockdown made me feel so useless. Being part of a creative, collective process is really so great,” he said. “I’ve only taken a total of four days off since October, but I am as happy as I am exhausted.” — Paroma Soni

NYC Covid-19 Total Positive Antibody Tests by Poverty Level

THE Shooting Range Worker

the Shooting Range Worker

Smiling faces return to Coney Island

“Having life being brought back is a very hopeful looking thing.”

![]()

On a cold, breezy day in early May on Coney Island’s boardwalk, a line of 16 black pistols and sarcastic red clown smiles all looked at the boss lady of the shooting range. Double masked and layering two, thick, polyester sweaters, the woman who yells at the players to fire, leaned over the shooting stand and smiled, looking for the next line of shooters through her fogged glasses perched just above her two surgical masks. With her small frame dwarfed by her Deno’s Wonder Wheel sweatshirt, she nervously wringed her hands and grinned as she explained the rules to each child while prepping each water gun for action.

3. 2. 1. FIRE!! The show began. Parents held up their kids on the six inch concrete step as they gripped the triggers. Hissing like a snake, water squirted out of the pistol’s muzzle to fill up the balloons on top of the clowns’ heads. Their siblings and friends shouted from the sidelines, their smiles half-covered by face masks. A balloon popped, eliciting cheers and groans, and the operator awarded the winner with a grand prize: a stuffed pink and white unicorn. After the fanfare was done and the kids had moved on, she sighed with relief; another successful game completed in her first three days on the job.

For native New Yorker Celes Perez, 24, a summer without Coney Island was almost unthinkable, until COVID-19 hit.

A Brooklynite and a resident of Coney Island for over 21 years, Perez felt an emotional toll on her neighborhood when the park remained closed last summer. Now, she’s going to spend the summer working at the shooting range as Deno’s Wonder Wheel Amusement Park ramps up its ticket sales for the new season. “When I found out from a friend who worked at the amusement park that they were looking for people to work there, I jumped on the opportunity to try something new,” she said.

“We have people that have been working here since they were teenagers.”

Although she’s only operated the shooting range part-time so far, working at Deno’s Wonder Wheel in Coney Island has revived Perez as she tackles this new opportunity. “Having life being brought back is a very hopeful looking thing,” she said, as she imagined the opposite being the case. “If the parks were shut down, I’d be extremely stir crazy and close to losing my mind.”

While Perez may be a newcomer to “America’s Playground” staff meetings, she hasn’t felt intimidated by some of her veteran coworkers. “We have people that have been working here since they were teenagers, you know, and they’re still working here today,” she said. “They’re one big team, part of our park. And everyone is so caring and loving to each other.” As the staff brought her up to speed on everything from ride maintenance to new COVID-19 protocols, she found the energy and enthusiasm to be a great fit. “I don’t know anybody who’s just like, ‘oh, gotta go to work,’” she said. “We’re all excited to be here.”

Unlike some of her co-workers whose work is primarily seasonal, Perez was, and still is, an essential worker at her second job at a construction site in downtown Brooklyn. But while she may have weathered the worst of the pandemic’s economic fallout, the empty souvenir shops and shuttered hot dog stands through the pandemic became a daily reminder of the pain the city was experiencing.

Her personal pain cut deep too. As a teen, Perez visited Deno’s Wonder Wheel frequently with friends and family, so the flashing lights and ringing bells were always a part of her. When the park shut down last March, she knew firsthand how bad the crisis could become for the peninsula if it went on. “Throughout the winter time, it’s a ghost town here. There’s nobody here,” she said, while cleaning and reloading the guns. “And for it to be like that for almost two years––was actually quite sad.”

For Perez, attending to the games at Deno’s Wonder Wheel may be the start of a new adventure, but for park administrators this summer will hopefully be a much-needed lifeline, even if they must operate at only 33% capacity. The 100-year anniversary of the park’s namesake ride was cancelled last summer when Governor Andrew Cuomo’s COVID-19 protocols prevented the celebration. The scheduled fireworks were out of the question. According to Dennis Vourderis, vice president of Deno’s Wonder Wheel Park, an anniversary celebration with fireworks this summer is “still up in the air” with no set decision due to pending permits from the city.

For an industry that relies on a seasonal boost to begin with, losing a full summer last year was devastating. And how this year will unfold is still uncertain. In addition to the limited capacity, the state also requires temperature checks and social distancing while on a ride. But longtime manager Steve Saross says it’s “just the way of life” now to stay in business.

Even with the added safety restrictions such as mandatory masks and increased wipedowns of rides, Perez and her team are happy to welcome the return of fun-seekers of all ages. The slow return to normalcy “feels like hope” for Perez, who wants to become full time later in the summer, and the excitement in the air and smiles on children’s faces is “what makes it home.”

“Our parks are made for little kids and we’re doing exactly what we advertise and other than you know COVID putting the tiny damper on our style, I wouldn’t change anything,” said Perez. Except maybe this: she aims to try her hand at operating everything in the amusement park, from the big rides to the bumper cars. — Christopher Alvarez and Madeline Renbarger

NYC Covid-19 Total Positive Antibody Tests by Sex

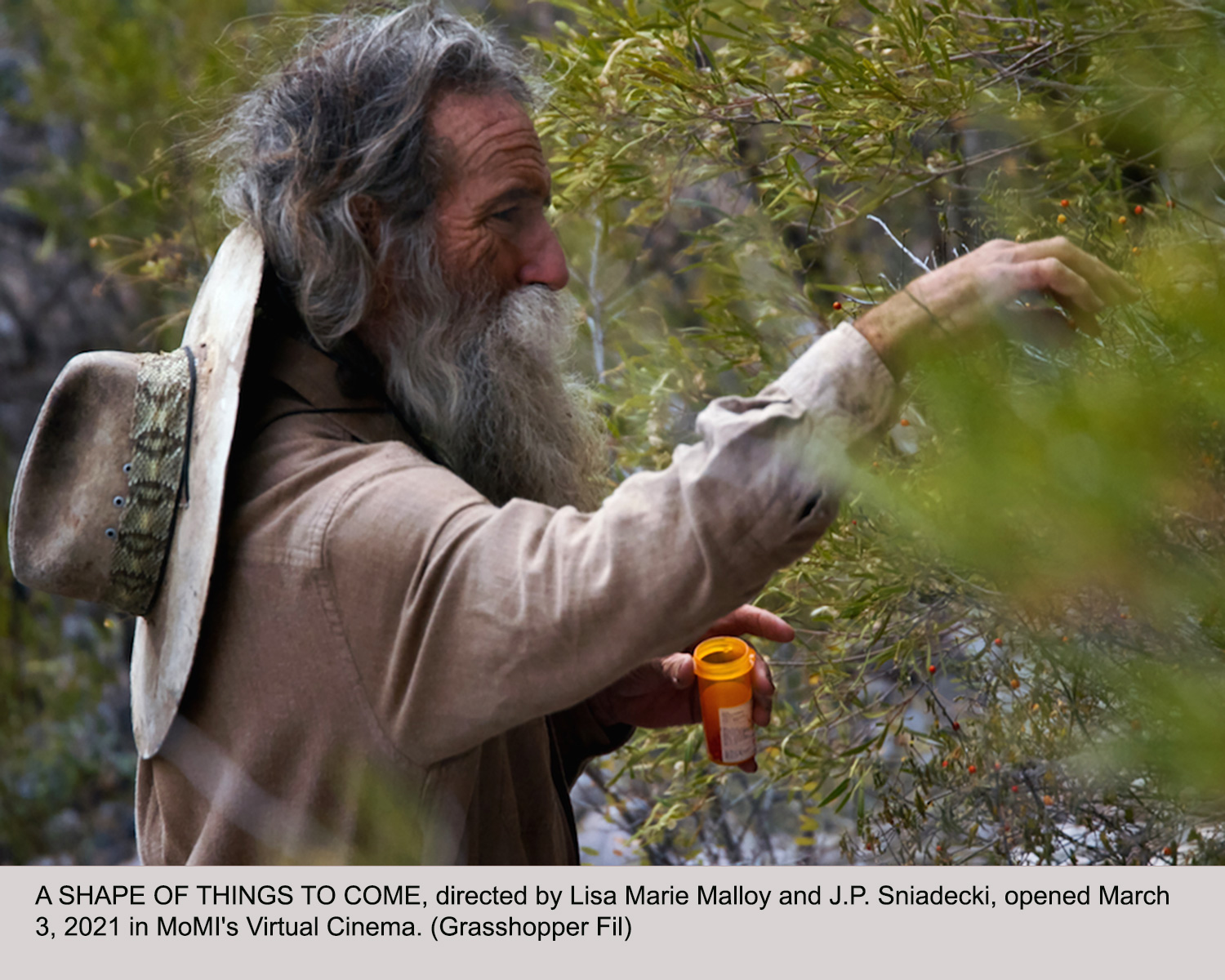

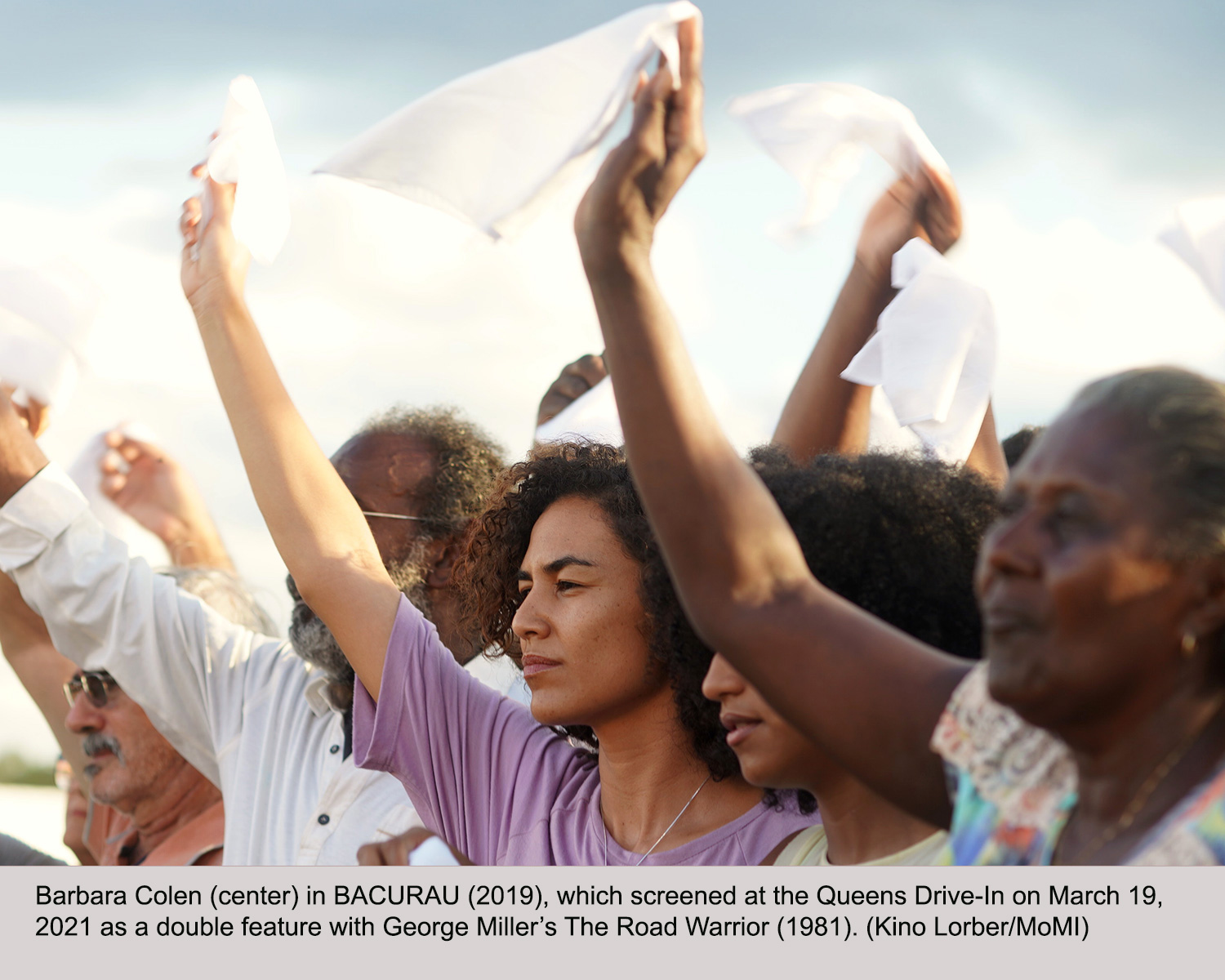

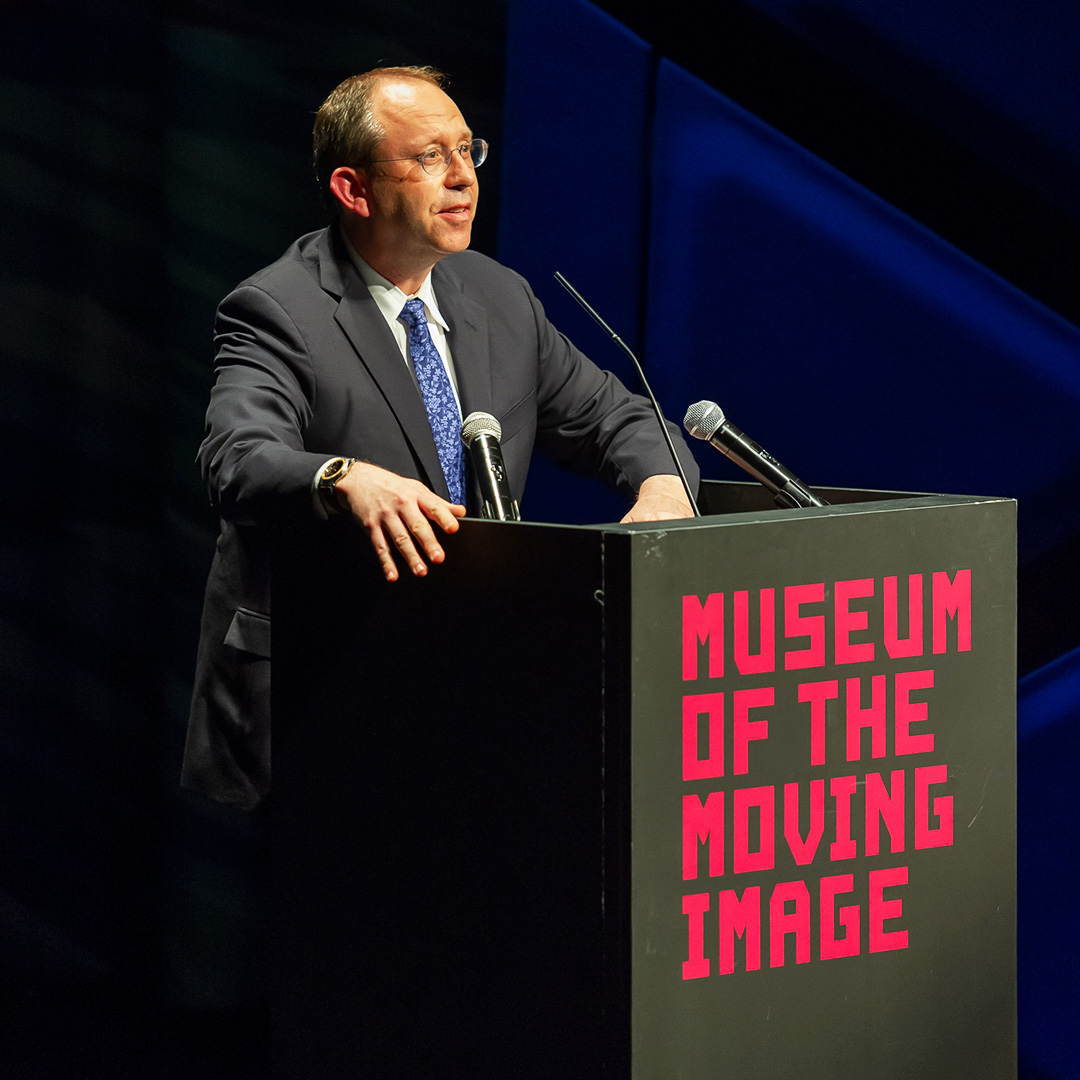

The Museum Director

The Museum Director

The Museum of the Moving Image, a movie Mecca, stayed afloat by changing

“We have to jump in, make mistakes, and bump into innovations.”

![]()

On a sunny Saturday in May, Carl Goodman took a deep breath behind his mask as he peered through his glasses at the long line of eager movie fans lined up outside the Museum of the Moving Image. After 14 months the museum, dedicated to the movie business, was about to reopen. Goodman, its executive director, watched little kids rush to see their favorite Muppet characters in The Jim Henson Exhibition, their parents marvel at the original props from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, and even a security guard tear up at the sight of smiling faces back in the once-empty building he had guarded through the long pandemic.

After the excitement of opening day passed, however, Goodman said, he had “no time for immediate gratification and laurel-resting,” as he put it. It was time to go back to the hard work of maintaining and growing a museum in our new hybrid world. The pandemic didn’t kill the museum, but it changed it.

Not that it was easy. Back in March of 2020, when the museum’s doors closed indefinitely, Goodman said he had to redouble his determination. For Goodman, the thought of losing the museum was so devastating that it wasn’t even an option.

As the pandemic dragged on, there was no telling when museum staff would be able to re-enter the building. So Goodman and his team began to find new ways to exist without a physical space. “As I said to my colleagues and even to funders, we don’t really know what we’re doing right now,” he said during a phone interview. “But we have to jump in, make mistakes, and bump into innovations.”

Jump and bump they did. When the world moved online, so did the Museum of the Moving Image. “We never closed,” Goodman emphasized. The shift was natural for him, he said, since he had previously worked as the museum’s curator and director of Digital Media and led an effort to digitize the museum’s entire 130,000-item archive. Instead of stopping the museum’s local after-school programs, for example, he helped to convert them into Zoom classes.

“I started calling our educators spelunkers.”

“I started calling our educators ‘spelunkers,’” he said of the remote tours. “They’d go down there, you know, with the camera and take people through.” Goodman also partnered with Rooftop Films and the New York Hall of Science to launch the Queens Drive-In, an outdoor screening series in Flushing Meadows park––a program that he says will continue. And to make up for massive losses of earned income, Goodman spearheaded a successful effort to get a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to update the museum’s website and live streaming capabilities. The museum’s budget is funded in part through grants like these in addition to ticket sales, memberships, donations, private foundation contributions, and city, state and federal funding, making these new programs vital for keeping it up and running.

Goodman is passionate about the museum— you can clearly hear it in his voice when he talks about it. He got his first job in the museum as a floor attendant back in 1989 and has since climbed his way up, while also working as a composer for film and theater scores. His love for his work came across as soon as he began to describe his 35-year history at the place: “I wasn’t really planning on staying, but it just kept getting more and more fun––until it got really bad,” he said, taking an almost theatrical pause while reflecting on the pain of this past year.

These days, Goodman is focused on what he sees as a “hybridized” future: as the city moves towards its goal of “totally reopening” by July 1st, Goodman says that the museum’s online programming is here to stay. “It’s not to replace what happens at the museum, but to augment what happens at the museum,” he says.

He’s hesitant to make any surefire long-term plans for the museum after this year, but he hopes that it will be around for a long time for New Yorkers from all walks of life to enjoy, including his own two children even if the museum, post COVID, will look and feel just a tiny bit different. –– Madeline Renbarger

NYC Covid-19 Percent With At Least One Dose

The Art Teacher

The Art Teacher

When the world slowed down, this Bronx artist sped up

“I can kind of catch up because I always felt like I was always trying to catch up.”

![]()

Janina Calabro, an artist born and raised in the Bronx, was talking on the phone on a Thursday morning in March with a friend that she hadn’t spoken to in a long time. “I know COVID hasn’t been great for everyone,” said Calabro to her friend. “But in a lot of ways, it has made us prioritize what’s important.”

And that’s exactly how it has been for Calabro. In the time of the pandemic, when the world seemed to slow down, Calabro says she sped up.

There have been ups and downs on her way to pursue a life with art, a life that would allow her to fully embrace its joy. COVID certainly felt like such an interruption for many, but Calabro took the pandemic as an opportunity to dive deep into the art world, work on her projects, and focus on her first passion — teaching art. During the shutdown, she continued her art-teaching job at Gym-Azing, a children’s party center in Queens, but also decided to dedicate more time to her own business, Sip and Paint, a birthday and gathering spot that she started two years ago. Sip and Paint allows people to meet up, paint, and share a drink.

“I hadn’t been able to put it together, like create the logo, and really push it forward. And that’s why I’m so grateful for COVID,” said Calabro. “I can kind of catch up because I always felt like I was always trying to catch up.”

She did, and also managed to kick everything in her life up a notch.

As the city shut down in March 2020, Colorful Talks, a nationwide non-profit organization that provides platforms for parents and kids to paint and talk about diversity, invited her to lead a “paint night” event once a month, via Zoom. One of the paintings produced on one of the nights was a portrait of multiracial kids running on the grass, laughing, and flying colorful kites.

“It’s like a giant whale’s eye watching me.”

“I’m Latina. So I understand a lot of the cultural stigmas,” says Calabro, who grew up in Levittown, Long Island. “I married an Italian man, so my children are biracial. I’m constantly talking to them about where my race plays in with this and the privileges that they have because their skin is fair.”

Calabro, 42, focuses mostly on canvas painting and murals and she says she’s inspired by the beauty of everyday life. She uses a wide range of colors to express harmony in a brave and creative way.

The artist recalls the Bronx of her youth as consisting of gray buildings with drug dealers outside of her school. But not everything was so dark and dreary. In her grandmother’s house in the Bronx, where she grew up, everything was colorful, she said, including the Mexican music her grandmother enjoyed. When she got back home from school, she remembers entering the house, shutting the door behind her, and feeling like she was in a totally different place. “It was like two worlds,” said Calabro.

Her appreciation of color traces back to her grandmother, but her love of art began when she was eight years old and her mother put her into an after-school program. At the art class, Calabro used to play a game where all the kids create a character together. One piece of paper would circle around the table and every kid got to add something to this character. In the game, she says, she remembers first feeling the thrill of creating her own art.

That passion lived inside of Calabro as she grew older, she says, and it felt free and therapeutic. Soon she found a way to share the joy that art had given her, by teaching it.

Even with the pandemic, she found a way to connect with others via Zoom. But she says she is still not so comfortable with the camera, because it makes her nervous. “It’s like a giant whale’s eye watching me,” she says.

She misses the personal interaction with her students, though. “Going around to each person and touching their shoulder and really trying to make them feel confident about their art and the process of it,” said Calabro. “I miss that.” As the city reopens, she hopes to be able to make it personal once again. — Xiang Shen

NYC Covid-19 Fully Vaccinated

THE ACTOR

The Actor

A Hamilton star enjoyed the pandemic break at first—until it went on, and on, and on…

“I realized that I was really mourning the loss of what I once was.”

![]()

The curtains closed and the lights dimmed on March 12, 2020, as Broadway shows suddenly shuttered, leaving many actors with a questionable future. One of them was Wesley Ryan, a tall, lean, Broadway actor who wore a bathrobe on his sofa during a Zoom call. He was fresh off a three-year-anniversary yacht party for the Hamilton tour, when he found out that the troupe was supposed to stop doing shows, supposedly for two weeks. Ryan and his roommate waited it out. Then it became six months. And then a year.

Ryan played Man 1 out of an ensemble cast of six in the Angelica Tour, one of Hamilton’s touring productions, a part that required him to act, sing, and dance throughout the entire show, much as he did for six years when he was in Disneyland theme parks in Hong Kong performing The Lion King, and In the Heights in Sacramento. Unlike most people who were worried about job security, Ryan admitted he liked the pandemic break at first, because “it was a nice change of scene.” Hamilton was a hard show to do eight times a week, Ryan said, so he took advantage of the time off and went home to Los Angeles to spend time with his mom, something he hadn’t done in years. When he wasn’t feeling well, he would go to the beach and feel better. He said he felt like he “skirted the COVID depression”— until late August last year, when everything came crashing down.

“It wasn’t until I moved back to New York,” Ryan said, that “the truest form of COVID depression hit. I was really just experiencing and living through the loss of so many things: my relationship, first and foremost at the time. This career — which I have worked my literal entire life for – gone, with no inkling of when it’s going to return.” When he moved back to New York in September, he stayed in one of his friend’s one-bedroom apartment and, he said, he’s been lucky—his unemployment benefits have been enough to cover the costs, thus far.

But Ryan was emotionally and psychologically affected by the pandemic, and he says he spent a lot of time struggling to find himself and get back to the joyful and creative state of mind he once inhabited. For a time, he could no longer find the energy to create and be creative. “I couldn’t do the thing that brings me the most joy. And one of the ways that really came about is that I had no desire to even be creative,” Ryan said.