Over the past few weeks, New York has experienced tremendous loss. Close to 20,000 New Yorkers have died of COVID-19 since the first reported death on March 14. Death has touched every community, has had an impact on every borough. And as the city continues to release data, and the numbers continue to rise, it’s important to remember that the statistics are just that, numbers. Behind every statistic is a person—a New Yorker—who touched other lives in ways big and small.

“New York is not numb. We know this is not just a number—it is real lives lost forever,” Gov. Andrew Cuomo tweeted on April 12.

Yet, while we mourn for those who have died, we also celebrate their lives as the people who helped make New York what it is. The virus has stolen the lives of teachers, bus drivers, chefs, doormen, police officers, of mothers, fathers, grandparents, and friends. With many families unable to hold proper funerals or memorial services, it becomes even more important to find ways to remember those we’ve lost, and honor them.

A report from The City and Columbia Journalism Investigations suggest that as few as five percent of New Yorkers killed by the virus have had their lives commemorated in the press. Our small newsroom cannot honor a great many of the close to 20,000 who have died, but we want to share the stories of some of them, a handful of New Yorkers who loved, lived, and breathed in this city, like so many others who have died of the same affliction. We want to remember them for what they gave us, how they touched others, and the memories they leave behind.

January 4, 1957 – April 26, 2020

An Emergency Room Matriarch

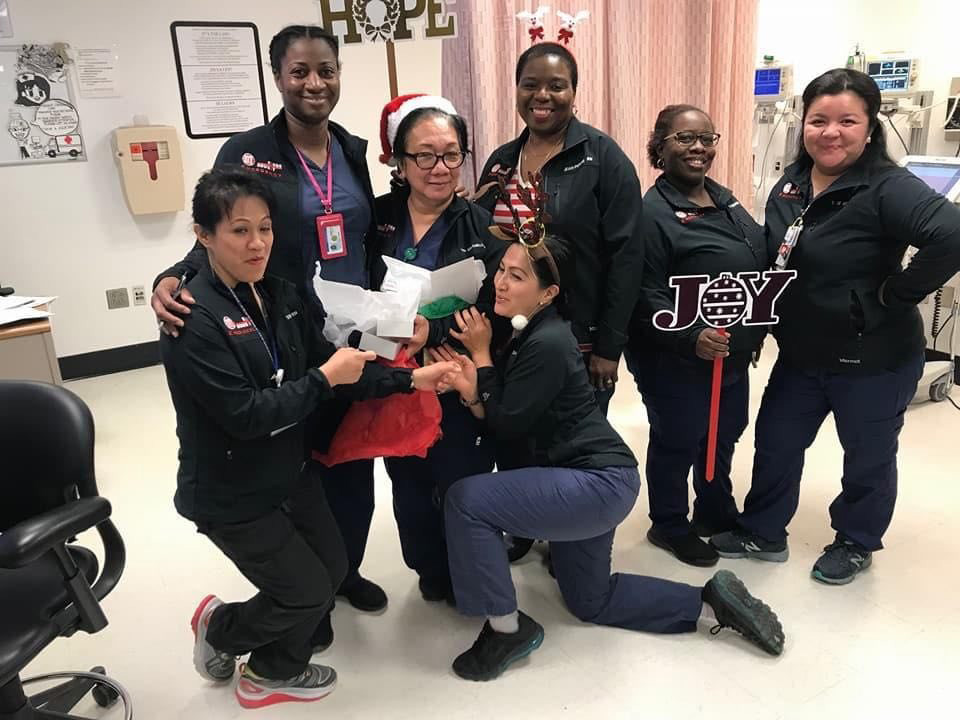

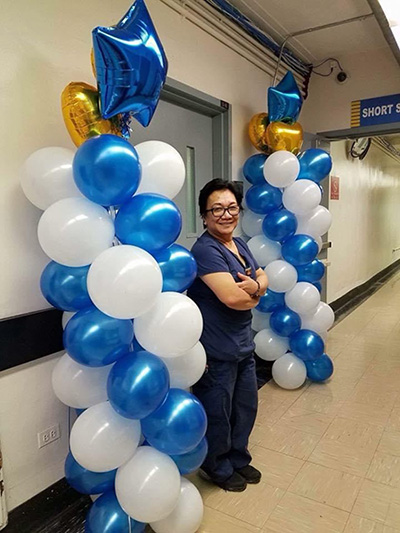

Maria Guia Cabillon at Kings County Hospital/Photo Courtesy of Fatima Eve Cabillon

If you’ve been to the emergency room at the Kings County Hospital in Brooklyn, you probably have heard the voice of Maria Guia Cabillon. You would hear her from down the hall and know that she was coming, even without seeing her, or you would hear her through the intercom system on your work phone. But now, the emergency room is quieter. Cabillon, the head nurse of Kings County Hospital’s emergency room, died on the afternoon of April 26 at the age of 63, after a long battle with COVID-19.

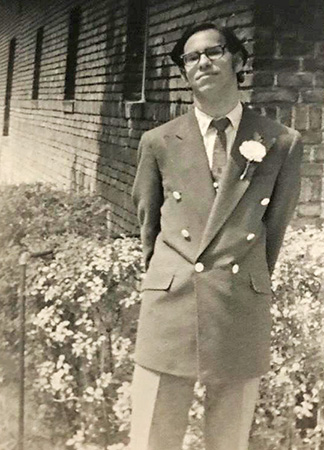

Born on January 4, 1957, Cabillon grew up with her three sisters in Iloilo City in the Philippines. Despite her aspiration to become a doctor, Cabillon chose nursing because her family couldn’t afford medical school. After graduating from the Corazon Locsin Montelibano Memorial Hospital/College of Nursing in 1979, she worked her way up to become a head nurse in the Philippines.

In the late 1980s, she decided to come to the U.S. even though she was already married and had three daughters. She wanted to provide a good education for her girls. “She said that we really had nothing back home,” said Cabillon’s daughter Fatima, who also became a nurse, under the influence of her mother.

Cabillon started at a nursing home and eventually landed nursing jobs at both Kings County Hospital and New York Community Hospital—she was still working at both places until she got sick at the end of March. Despite being a small woman, just five feet tall, Cabillon was brave and feisty, according to both her daughter Fatima and her colleague, Shane DeGracia. She was able to stand up to violent patients who were having psychotic breaks and calm them down. Having gone through SARS and Ebola, Fatima says, she was not afraid of COVID-19. “She says, ‘well, you’re a nurse, you have to be brave. You have to think about these patients, that they need you,’” said Fatima.

If it wasn’t for COVID-19, Cabillon could have retired in two years, after more than 30 years of nursing. But DeGracia says Cabillon loved her job so much that she didn’t seem to want retirement. “Honestly, I didn’t think she was gonna retire when the two years came. I don’t see it in her to leave the emergency room,” said DeGracia.

“She was the anchor. She’s the captain of that ship and really tried to do smooth sailing, despite rough waves.”

Shane DeGracia, ER Nurse, Kings County HospitalAs the head nurse, Cabillon was the one who held the emergency room together—and made it a home. Everyone called her “Mama Guia,” or “Nanay,” which means “mom” in the Filipino language of Tagalog.

She loved everybody unconditionally, DeGracia says, and took them under her wings as if they were her own children. Apart from being a mentor in the nursing field, she was the one that people turned to when they had personal problems; she was the one that former co-workers from the early 1990s would still visit; she was the one that police officers from the 71st Precinct were familiar with.

Cabillon was also a foodie and made sure her ER children were well fed. There were always chocolate, seasonal candies, Cheez Doodles, and bottles of Mountain Dew on her desk. She would make Filipino adobo, her favorite dish, and share it with doctors and nurses.

“She’s the mother head,” said DeGracia. “She’s the matriarch of our ED.”

On the night before Cabillon was admitted to hospital, she called her staff and asked one of them to switch the time sheets so that the incoming shift was able to sign them. “Instead of resting at this hour, she was thinking about work,” said DeGracia, “She was thinking about making sure that people get paid, and that they’re able to clock in and out.”

Caibillon was also a patient advocate, her colleague and daughter say. If an ICU patient needed a bed, she would try to make sure the patient got a bed; when patients were assigned beds upstairs, she would be on top of it and make sure they were sent upstairs in a timely manner.

“She was the anchor. She’s the captain of that ship and really tried to do smooth sailing, despite rough waves,” DeGracia said.

If you go to Kings County Hospital’s emergency room now, you won’t be able to hear Cabillon’s big voice and laughter, or her saying “I’m going to kill you” in a joking way. But she will forever remain a guiding light to the ER.

Maria Guia Cabillon is survived by her husband Roberto; their four daughters, Fatima, Grace, Francine, and April; and two grandchildren, Francesca and Sean.

January 15, 1952 – April 3, 2020

The Mayor of Court Street

Albert Rahey’s family remember him as a man with a big heart, a big personality, and a big mouth. Al died of COVID-19 on April 3, just as he was preparing to go home after surgery on his leg, at age 68.

Albert Rahey’s family remember him as a man with a big heart, a big personality, and a big mouth. Al died of COVID-19 on April 3, just as he was preparing to go home after surgery on his leg, at age 68.

Al, often called Big Al, knew everything about everyone. He was known as the “Mayor of Court Street” in his neighborhood in Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn, because he was the one everyone would go to for information.

“He was a talker,” Carol Montalbano, his long term girlfriend said. “You would think he was a gossip, but it’s not a negative thing. He would just know everything that was going on and people would come to him for information and help.”

At reunions and family gatherings, he was the life of the party. Once, at a family member’s sweet sixteen party, he jumped up on stage sporting a leather jacket and sang Doo Wop songs. He preferred the Moody Blues, his favorite band, though.

He could be meticulous. For example, Al planned his daughter’s wedding down to every detail. He had a box for the invitation replies, all neatly alphabetized. But he could also be carefree: Al tended to leave all the lights on.

He was born in Brooklyn and attended John Jay High School, where he played baseball, the number 17 emblazoned on his jersey. He had unshakable loyalty to the New York Yankees, and also to the New York Jets.

He enjoyed cooking, and he especially liked making Syrian stuffed grape leaves with his daughter. He was a gambler and loved playing scratch-offs and watching horse races, so much so that he once co-owned a racehorse named Sneaky Girl in Saratoga. She never won until after he sold her, Al’s family said.

Al served in the Navy during the Vietnam war and earned the rank of Seaman. He later became a building maintenance engineer.

“You would think he was a gossip, but it’s not a negative thing. He would just know everything that was going on and people would come to him for information and help.”

Carol Montalbano, Long-term girlfriendLater in life, he spent countless hours at the St. Nicholas Antiochian Orthodox Cathedral in Brooklyn. He was considered the priest’s “right-hand man,” and would set up for funerals and weddings.

While tidying up the church basement in January, Al tripped on a mat wet with snow and shattered his femur. After having surgery, he went to the Richmond University Medical Center Rehabilitation Center on Staten Island to be closer to his daughter, Sheriann Rahey-Callahan, while he underwent rehabilitation. He was in recovery for nine weeks, and those who know him say he anxiously awaited discharge so that he could get back to his family, his neighborhood, and his church. He did extra exercises on his own to try and hurry along his recovery, but three days before he was supposed to be released, he got a fever. About a week later, he died of COVID-19.

At his funeral, watched on Facebook by more than 1,600 people, Father Thomas Zain said that he is happy that his friend is “home now,” he said.

“There are no more broken bones or infected lungs. No more sorrow about the state of this broken world. No more sighing about when he would finally get to go home but rather eternal life in the permanent home free of all diseases.”

While in rehabilitation, Al had been looking forward to his yearly trip to Aruba, where he and his sister owned a timeshare. He had purchased his ticket in January. Al and his sister had a group of friends who affectionately referred to him as “Aruba Al.” Over the years, the group expanded to about 20 people, according to Al’s longtime girlfriend, Carol. All of them had met through Al, Carol said, because he would warmly say hello to each of them at the bar.

“He was just so full of life. He enjoyed everything about life and put 1,000 percent into it,” Carol said. “Everyone who met him instantly loved him,” his daughter Sheriann added, “he just had that personality.”

May 18, 1962 – April 13, 2020

A Loving Teacher

For those who worked with Fatima Schmidt for the past 15 years, walking by her fourth-grade classroom of Public School 333 in the Hunt’s Point section of the Bronx, will never be the same. She died on April 13th from COVID-19. She was 57.

A curly short-haired woman, with light brown skin, and brown eyes that would shine through her rounded eyeglasses, Fatima Schmidt was a selfless genuine, kind, and motherly woman, according to those who knew her well. Her colleagues describe her not only as a teacher but as the most passionate soul that reminded all students to move forward and achieve their goals against all odds.

“She would always fight for the best of her students,” said Betty Gerassi, who worked with Fatima since 2009 and remembers how Schmidt would stand up to advocate on behalf of her students at Board of Education meetings. “She was very vocal about the books or resources our students needed.” Gerrasi said she was particularly indebted to Schmidt for supporting and believing in her. She “became like a mother, a mentor, a great friend,” said Gerrasi.

Jaime Barron another teacher who worked with Schmidt for 14 years, said she spent more time outside of work with Fatima than with her own family members. Schmidt and Barron planned lessons together and according to Barron, Schmidt volunteered for other classroom activities too. “She would go and buy pumpkins, dresses, or simply help out organizing for the 100-day celebration of kindergarten students, every year,” remembers Barron.

“I will never forget her big smile and her even bigger heart, full of gratitude.”

Betty Gerassi, ColleagueBoth Borran and Gerassi recall the many times Schmidt would go around their classrooms during breaks to share snacks or the delicious desserts, she would bring from home.

“I liked her habichuelas con dulce,” said Barron, referring to a famous dessert from the Dominican Republic made of beans, sweet potato, raisins, and milk that Schmidt would bring every year during Lent.

Gerassi even remembered that thanks to Schmidt, she would eat foods that were better for her. “She would come and say, ‘Do you want a banana?’ I am not a fruit person, but she was so diligent looking out for me that I would say, yes,” said Gerassi.

Fatima and her family in Europe last year. Courtesy of John Schmidt

Fatima also built a great relationship with her colleagues outside of work.

She would host a barbecue at her house for her colleagues during the summer and everyone would bring different dishes. She always wanted to be part of the important moments of her colleagues. Gerassi recalled that after a long day at work on her birthday in 2018, her colleagues, including Schmidt, improvised a get together at Jimmy’s restaurant in the Bronx. “She made it a priority to be at my 36th birthday full of laughter. It was the last time she sang ‘Happy birthday’ to me,” said Gerassi.

“I will never forget her big smile and her even bigger heart, full of gratitude,” said Gerassi who will extremely miss Schmidt, her teaching ideas, and her positivism once they go back to the classrooms.

Fatima Schmidt was the firstborn in the Castellanos-Peralta home, a modest family of farmers from the town of Tamboril in the city of Santiago, located in the center-north region of the Dominican Republic. When she was 7 years old, her family moved with her and her two younger sisters to start a new life in the United States. They settled in Washington Heights, New York, where her younger brother was born. Fatima was a very bright, energetic, and driven child who always looked for new ways to learn no matter the obstacles she faced, says her husband, John Schmidt, who met her when they were students at Inwood Junior High School 52 when she was 13 years old and he was 14.

“She got two bachelor and two master’s degrees,” said her husband, 58 who spent 44 years with Fatima and had two children: daughter Karin and son Johann, now young professional adults.

“She was always concerned about our kids’ education and was always there for them,” said her husband. He recalled how willing his wife was to drive to see their son during diving competitions while he was in college in Massachusetts. “ No matter the weather, she would go to the sports events sometimes twice a week, drive four hours, be there for two hours and drive four hours back the same day,” he said, adding that his son had told him that many times she would be the only parent there.

Schmidt also added that he admired his wife’s devotion going above and beyond for their children even though she had a full-time job. At the same time, she gave so much to her students in the Bronx, he said.

Layla Franco, 15 a former student of Schmidt says she will always remember the caring and very strict teacher who shaped her to become a great student. “She made us work hard, reading complex books, and taught us how to write excellent essays,” said Franco, who added that she kept in contact with Schmidt until recently. “She always asked me how I was doing and what I wanted to study in college.”

According to her husband, Schmidt had the opportunity to work in private schools or in the suburbs of Rockland County, where they moved 30 years ago but instead, she decided to work in the Bronx with kids who had similar learning experiences as she did as an immigrant and first-generation student. “She saw in every student, the struggles she went through,” he said.

She even joined a charity to help communities internationally provide a sound education for children.

Courtesy of John Schmidt

For the past 12 years, the couple sponsored many kids in an educational program in Honduras, where John was originally from. She used to travel with her own kids to help the communities in need and share her teaching expertise.

Mr. Schmidt and his family have created an organization to look and provide learning resources for children in communities that need help most, just as she would have done.

“We want to honor her memory helping poor kids to empower themselves through education just as my wife did,” Mr. Schmidt said.

On April 13, before putting on a ventilator, Fatima was able to see her family through video, and John’s last words to her were to stay strong and that she was going to make it. In his view, the charity’s mission to help kids learn will ensure that her loving spirit will live on.

By Angie Hernandez

August 29, 1951 – April 10, 2020

La Puertorriqueña

Even though she left Puerto Rico to come to New York City when she was 15 years old, Ana Santana lived a life steeped in the vibrancy of her home country. Her effusive warmth, love of beaches, and penchant for singing salsa songs by Héctor Lavoe and El Gran Combo had been engrained in her and remained so until she died on April 10, 2020, after contracting COVID-19. She was 70 years old.

“When I feel a certain type of way, that’s what I listen to,” said her daughter, Odalis Santana, 46. “And when I listen to it, I know she’s with me.”

Santana was born on August 29, 1951 in Bayamón, a small coastal municipality in Puerto Rico. She emigrated to the United States in 1966, and worked at a clothing factory in New York City, sewing colorful pieces of fabric together into blouses, skirts, and trousers.

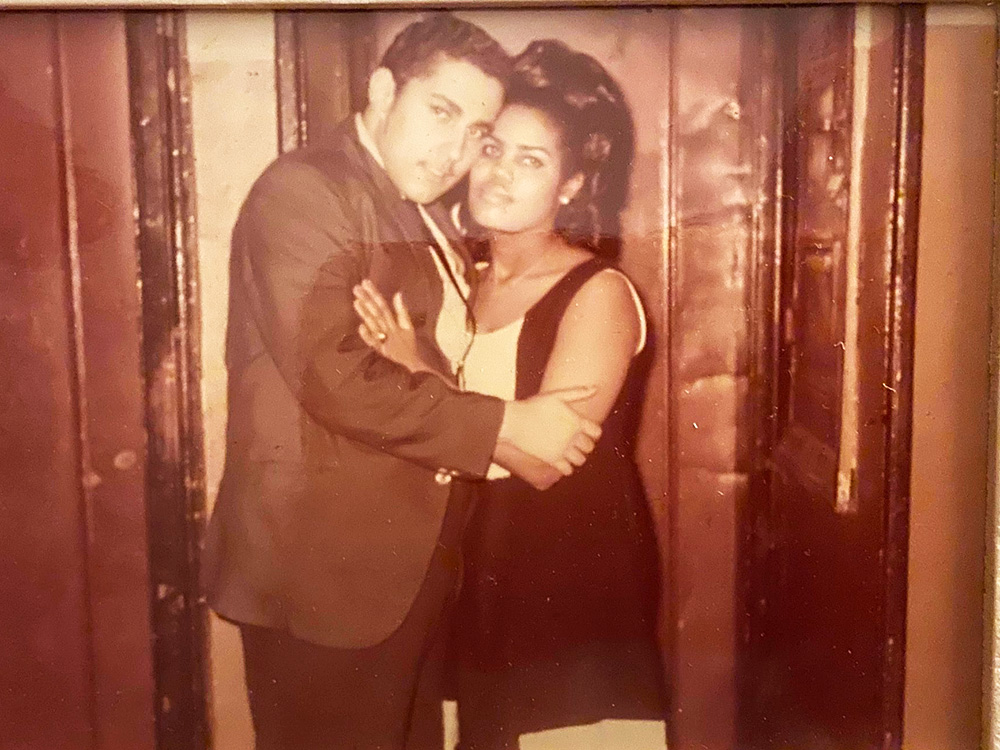

Ana Santana / Photo courtesy of Odalis Santana

She went to church every week. There, in the late sixties, she met Osvaldo Santana, a dark-haired fellow Puerto Rican who grew up in the Bronx, when they were both teenagers. The couple married on October 23, 1971 and shared 42 years of marriage together, spending many evenings at social events at church dancing, especially salsa, which was Santana’s favorite.

Santana lost her husband to interstitial lung disease on October 30, 2013. She developed even deeper and closer bonds with her son, Jose, now 37, and her daughter, Odalis, who said her ties to her mother went beyond a typical mother-daughter relationship.

“She loved to talk, talk, talk, talk, talk,” said Odalis, especially when it came to two topics: Puerto Rico, which, in her heart, always remained home, and her two grandsons, Dylan, 12, and Logan, 8.

“She had an energy to attract people to herself. She was a motivator, who brought family and others with her.”

Father Babadudu Ucheo, Our Lady of Hope ChapelOdalis said her mother loved big gatherings, because it gave her the opportunity to be chatty and catch up with all those that she loved. Every Thanksgiving and Christmas, Santana would gather everyone for a bustling celebration, complete with music—salsa, of course—and abundant food. She always cooked enough arroz con gandules, a Puerto Rican dish of fragrant, seasoned rice with pigeon peas and pork, to last another three days as leftovers.

Others also found comfort in Santana’s maternal presence, including Eva Anel López, a close friend of Odalis since high school. López, who lost her own mother as a child, said that she felt that she’d found both a mother figure and a friend in Santana.

“She was always listening, even when you thought she wasn’t,” she said, remembering once when Santana would recall “a jerk” López had once pined over when she was younger. As adults, Santana, Odalis, and López went to Orchard Beach in the Bronx every summer, enjoying the warm sand and glittering ocean while their children were at summer camp.

Close friends and casual acquaintances alike agree that Santana was a vibrant, kind, and giving person, who was especially passionate about supporting children through donations to St. Jude. Santana’s generosity was returned with love from the community.

The Santana family at a birthday celebration (l), Odalis and Ana Santana at the beach (r) / Photo courtesy of Odalis Santana

“She had an energy to attract people to herself,” recalled Father Babadudu Ucheo, chaplain at Our Lady of Hope Chapel in the Bronx, where the Santanas attended mass most Saturdays. “She was a motivator, who brought family and others with her.”

Even when Father Ucheo visited Santana at the Albert Einstein Hospital, where she was admitted after she was diagnosed with COVID-19, he was struck by how full of smiles she was. Six days later, on the morning of Good Friday, April 10, Ana Santana died due to complications of the virus.

When the pandemic is over and travel restrictions lifted, Odalis and Jose plan to go to Puerto Rico—the place that never left their mother’s imagination—to scatter her ashes. “It’ll be in the ocean,” said Odalis. “She always loved the beach. She’d just love it.” Maybe they’ll play some salsa songs to send her off, the Santana way.

By Yoonji Han

September 4, 1952 – April 4, 2020

Beloved Bookseller

If you worked or lived near Columbia University, you probably knew Steven J. Hann. Maybe not by name, but if you walked along Broadway near the university, he was hard to miss—a 5’5” white man in his 60’s, wearing small squared glasses and showing his half bald gray-haired head shining above a welcoming smile and twinkling eyes when people asked him about his books. For more than 20 years, Hann sold second-hand books in front of Milano market near the school.

Hann, died on April 4 from an unknown heart complication, according to his younger brother, Mark Hann. “He had COVID-19, but was asymptomatic,” Mark said. Hann was 67.

Many of his friends remember the longtime bookseller as a deep thinker, hard worker, and a man who cared about people. He loved talking about politics, life, and mostly about his deepest passion: books.

Photo courtesy of Olivia Hann

“We would debate politics every single morning, for like 45 minutes,” said Dominick Galofaro, manager at Milano, who knew Hann for 18 years. “He always told me don’t argue when talking about politics.”

“I remember asking Steve, ‘how do you know that, Steve’? And he would say ‘because I read.'” Galofaro says he will miss looking outside of the window at Milano’s and watching Steve’s face and eyes light up as he read.

Milano’s catering coordinator, Jonathan Diaz, 28, says he was probably the last person at the market to talk with Hann before he died. He wishes he could have said many things to him before he hung up. “He said, ‘I won’t come back. And I said what do you mean?” said Diaz, who added that he’ll never forget that conversation. Hann answered, “I just won’t come back,” but Diaz was busy at work and remembers telling him, “Steve, please call back later, and we will talk more.”

“What I liked the most about him was that he cared about people,” said Diaz, who says he bought 10 books from Hann during the four years he knew him.

Luigi Kapag, 67, said he met Hann in the late 1990s while selling appointment books at a stand situated right next to Hann’s. This was at a time, he said, when appointment books, and not smartphones, helped organize a person’s activities.

Courtesy of Jessica Hann

Kapag said he and Hann became best friends. Six days a week, he remembers, he would carry Hann’s books from his van to his sidewalk table, where Hann would sit, wearing his beloved jean jacket and black hat. “I used to call him smurf because of that black hat,” said Kapag.

According to Kapag, Hann in his 20s used to play the guitar in a rock band, one that was better known in Europe than in the United States. He knew a lot of musicians from that time, said Kapag. “He had a picture with Jim Morrison from the Doors.”

Steven J. Hann was born on September 4, 1952 in the Bronx, and from an early age enjoyed his three main passions: music, reading, and writing, and spent more than 20 years doing what he loved the most, selling books.

Hann never got married or had children but was very close to his nieces, Jessica and Olivia Hann. According to his niece Jessica, Hann wrote books, and one called “the brat” was dedicated to her. “I was an only granddaughter for ten years and his book was about a little girl who always got in trouble just like me,” said Jessica. She enjoyed one time going to see him at a book reading, which he did once or twice a month.

One thing her uncle always told her about was his desire to go visit his good friend in Australia, Katie. “I am sad that he wasn’t able to go on that trip to be with his friend,” said Jessica.

His youngest niece, Olivia Hann, says she used to speak to him once a week. They shared a passion for reading and she loved that he knew a lot about music. “He was constantly creating, constantly writing, and I really liked that,” said Olivia.

“I used to call him smurf because of that black hat.”

Luigi KapagAccording to his younger brother, Mark Hann, for the past three months, Steven was living in a nursing home, and was in Montefiore Hospital for more than three weeks before he died on April 4th. Steven had a medical history of heart failure and had open-heart surgery in the 1960s. He was also a colon cancer survivor.

His family and friends say they want people to remember Steven Hann as a man who loved what he did—selling books and meeting people, especially students from Columbia University.

To his niece Olivia, the best way to honor Steven is “to read more and to be well informed.” By Angie Hernandez

August 30, 1968 – April 24, 2020

The Gentle Pasta King

Rosas “Miguel” Grande, 51, always knew exactly what kind of flowers to get his wife—on Valentine’s Day, on her birthday, on Mother’s Day. The flowers were always different—this past Valentine’s Day, it was a handful of green orchids. Through all their years of marriage and the births of their four daughters, Grande was consistent in everything he did: never missing work, never missing a rent payment, never missing a chance to bring his wife flowers.

“He was always responsible, no matter what,” says Maribel Luna, Grande’s wife.

Grande, who died on April 24 of COVID-19 complications at Elmhurst Hospital in Queens, was also committed to his job as a pasta maker at Supper, a restaurant in the East Village. He’d often bring home leftovers to his family—his wife, Maribel Luna; four daughters, Guadalupe, 27, Erika, 26, Yulisa, 19, and Emily, 16; and four grandchildren, Angel, Aiden, Ryan, and Rose.

At work, he was the “Pasta King,” known for an uncanny ability to make the most decadent pasta, which he would sometimes bring home to his family. If you had pasta made by Grande, “you had a dish made with love and honesty,” as the GoFundMe page set up by his employer explains. The fund has already raised $22,205 in donations.

At Supper, Grande was famous for his big smile, his love of pasta-making, and his joyful outlook. Co-workers said you could taste that love and joy in his pasta— that’s why it tasted so good. “Every day, for 17 years, we used to dance together,” says David Garcia, 34, who worked with Grande at Supper. Garcia would arrive at work, and Grande would greet him by turning on Spanish music. The two would dance for a few minutes—a small moment of joy.

Making pasta was a logical progression for Grande, who worked with his hands from a young age, first as a baker for a company that eventually relocated to New Jersey, and later, as a cook. His daughters will remember Grande best, they say, for his Sunday morning feasts—and his incredible eggs. Every Sunday, after taking his two beloved dogs, Max and Winter, for a walk, Grande would make omelets and bacon for his family. The secret ingredient that made his eggs taste so wonderful? “He always made it with love,” Guadalupe writes in an email.

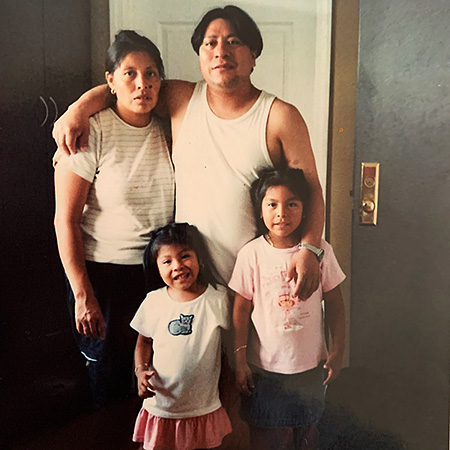

Rosas Grande Gomez was born on August 30, 1968 in San Martín Tlamapa, Mexico. The eldest child of eight siblings and step-siblings, Grande was the backbone of his close-knit family. “Every Christmas, every new year, we were always together,” Guadalupe says. When he was just sixteen years old, Grande left home to work in New York, sending money home to his family in Mexico. For 34 years, he supported his family in the states, and those back in Mexico.

“He was living the American Dream, providing everything for his kids,” says Miguel de la Rosa, Erika’s husband. Grande was in the process of becoming an American citizen when he died.

But even after 35 years, he still missed Mexico—and planned to return one day and live in a house he was building there. “He always wanted to go back,” De La Rosa says, adding that after Julisa and Emily graduated from high school, he’d talk about going back and bringing his beloved dogs, Max and Winter, with him.

When he wasn’t working at Supper, Grande was at home, checking in on his girls, or walking his dogs. He was so close with his grandchildren that they called him “daddy” not “grandpa,” Guadalupe said. He was also fiercely protective of his four girls, often sitting boyfriends down to talk about their intentions.

At the dinner table, Grande would tell Mexican folk tale myths and discuss paranormal activity with de la Rosa. Grande loved asking de la Rosa if he believed in the ghostly tales. He also loved watching wrestling programs. For WWE’s Monday night “RAW” show and Friday night smackdowns, de la Rosa says, Grande would be “stuck to the TV.”

Grande, his wife, and two of his daughters./Courtesy of Guadalupe Luna

On the job./Courtesy of David Garcia

Grande always brought his wife flowers on special occasions./Courtesy of Guadalupe Luna

Yet, despite his love for the rough sport, Grande was a calm and gentle man. His daughters remember him dancing—holding the paws of their two dogs or the chubby hands of his grandchildren— pulling funny faces to make them laugh, softly teasing them with his own private nicknames.

Grande teasingly nicknamed Guadalupe “Chubby” or “Gordita,” and would peek his head into 16-year-old Emily’s room in the morning before school to tell her she didn’t need to wear makeup. ”You don’t need to wear that, you’re always beautiful,” Emily says he would tell her.

He would often check in on his daughters—even the adult ones—to make sure they were okay.

When Erika worked late, Grande would call her to see where she was. When Yulisa received a good grade in school, he was the first person she wanted to tell. Yulisa would run to him, and he’d smile his big smile, telling her “échale ganas!” Work hard.

Even as he was being carried into an ambulance, Grande thought of his family first. “Échale ganas,” his daughters told him. Give it your best. Come back home. Grande assured them that he would come back as soon as he could. Sadly, he didn’t. By Currie Engle

“Every day, for 17 years, we used to dance together.”

David Garcia, Colleague at SupperDecember 22, 1945 – April 14, 2020

The Devoted Doorman

When you walked through the glass doors of the Bel Canto Condominium on the Upper West Side before the pandemic struck, you would’ve been met with the bright smile and baritone greeting of Tony Torres. Dressed in his uniform of grey tie, white shirt and black suit, Torres was a doorman at the apartment building for 27 years. On April 14, 2020, he died due to complications of COVID-19, leaving the gleaming lobby of the Bel Canto a little emptier, duller. He was 74 years old.

“Everyone loved Tony,” Shirley Torres Calloway, Torres’s partner, said. “He brought so much joy to so many people.”

This included the residents and staff at the Bel Canto, where Torres started working as a doorman in 1993. Many describe him as a “giant” of a man, both in stature—he was 6 foot 3—and in presence. “He represented his profession with pride,” remarked Calloway. “He represented the true meaning of what a doorman was.”

Torres always greeted everyone with a warm smile, and never missed a day of work, except for when he had a stroke and had surgery for colon cancer a few years ago.

“As much as I wanted him to retire, I also didn’t want him to,” remarked Nick Pisco, the resident manager of the building. Pisco remembered that Torres played jazz music—his favorite station was the WBGO jazz radio station—in the lobby every Saturday morning, when passersby would stop for a chat.

Antonio “Tony” Torres/Courtesy of Barbara Torres Squires

“He was the voice, heart and soul of the Bel Canto,” Pisco said.

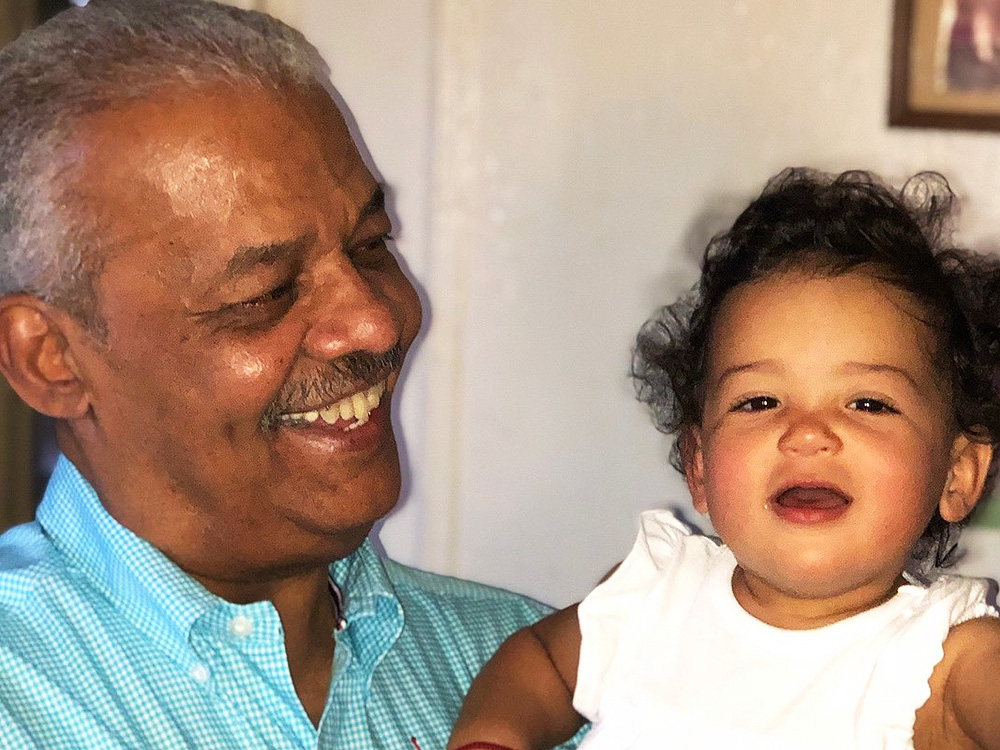

Torres was also adored by the building’s pets, for whom he always had treats, and was especially a delight to the children. Fotis Papagermanos, a resident at Bel Canto who’s known Torres for more than ten years, said that his four-year-old son loved Torres so much that he took to calling every doorman “Tony.”

“It was like a family relationship,” said Papagermanos. “He was like the grandpa of the building.”

Torres himself saw the residents at the Bel Canto as his kin. “It wasn’t a job to him. He was himself there, just like he was at home,” said Barbara Torres Squires, 64, Tony’s youngest sister.

Antonio “Tony” Torres was born on December 22, 1945 in Aguadilla, a beachside city in Puerto Rico. He moved to New York City with his parents, Eddie and Modesta Torres, when he was three years old.

More than 35 years ago, Torres met Shirley Calloway when he worked as an administrator at the pediatrics department of Lincoln Hospital in the Bronx. She was immediately drawn to his genuine, jovial nature, and, later, they got married.

He was just as loving and generous with his real family as he was with his adopted family at the Bel Canto. Both Torres and Squires moved in to their mother’s apartment in the Bronx to care for their mother, who is now 97 and suffers from Alzheimer’s and arthritis. Their brother Rafael, 70, lives in the same borough, while their other brother, Miguel, 72, resides in Florida. Tony has eight nieces and nephews, along with many grandnieces and grandnephews.

“He was the anchor of the family,” said Squires, Tony’s sister.

“He was the voice, heart and soul of the Bel Canto.”

Nick Pisco, Bel Canto Resident ManagerTorres never let his sister do the dishes, which he knew she hated to do after a long day at work. Dirty plates wouldn’t even make it to the sink before Torres, armed with Brillo and liquid soap, would swoop in to take them off his sister’s hands.

The two siblings always joked around together. “If I said a joke, he got it, and if he said a joke, I got it,” laughed Barbara, whom Torres affectionately called “Chiquie”—a variation of “Chiquita,” which means “small girl” in Spanish. Even with Barbara in her 60’s and Tony in his 70’s, they were “like teenagers” in the house. “We didn’t age here,” she said.

The TV at the Torreses’ house was always tuned to the news channel, especially when it came to politics. Torres was an avid reader, and, in addition to jazz, enjoyed Latin music, like those sung by Tito Puente. He also listened to gospel music every Sunday. “Take Me to the Altar” was his favorite song.

Intellectual and spiritual predilections aside, Torres also loved to eat. His dish of choice was pasteles, a Puerto Rican classic made with pork and plantains, which his mother used to make for him. But no matter what his sister, Barbara, cooked, he’d declare it “delicious.” Torres had a huge sweet tooth and would often return home laden with boxes of pie, cookies and cake. Sometimes, it’d be treats that Bel Canto residents had given him—just another way they showed their affection for the man who made their apartment building feel like home.

“He was a true gentleman who treated everyone with respect. Everywhere he went, he’d make friends,” said Calloway. Together, they travelled to Bermuda, Spain, Barbados. “Except he didn’t like flying too much,” she laughed. “He’d always need to take a deep breath… right before the plane took off.”

Tony Torres, who served in the U.S. Navy and fought in the Vietnam War, was laid to rest in the Calverton Memorial Cemetery on May 7, with honors. By Yoonji Han